Spring into Summer Conference at Portsmouth Institute, by Justin Katz

Religion

8:15 AM, 04/15/13

If Spiritual Battles Gave Off Sparks, by Justin Katz

Religion

7:54 PM, 03/31/13

Fish on Fridays, by Carroll Andrew Morse

Religion

11:59 AM, 03/29/13

Re: Keep Christ in Christmas, but the Government Out, by Carroll Andrew Morse

Religion

12:15 PM, 11/30/12

The Messiah May Have Used the Word "Wife", by Justin Katz

History

2:07 PM, 09/29/12

Things We Read Today (15), Thursday, by Justin Katz

Civil Liberties

7:50 PM, 09/20/12

Rev. Rich Takes a Stand Against Small Children, by Justin Katz

Culture

10:14 AM, 09/ 1/12

Portsmouth Institute, Day 3: Rev. Nicanor Austriaco, "What Can Genomic Science Tell Us About Adam & Eve?", by Justin Katz

Science

6:54 AM, 07/11/12

Portsmouth Institute, Day 2, Session 4: Dr. Michael Ruse, "Making Room for Faith in an Age of Science", by Justin Katz

Religion

6:20 AM, 07/10/12

Portsmouth Institute, Day 2, Session 3: Kevin O'Brien as Dom Stanley Jaki, by Justin Katz

Religion

6:53 AM, 07/ 9/12

April 15, 2013

Spring into Summer Conference at Portsmouth Institute

With spring more or less undeniably having arrived, we're coming up on one of my favorite weekends of the year. This year, the Portsmouth Institute's annual conference is June 7-9, and the topic is "Catholicism and the American Experience," which is certainly timely, given that American bishops are actually beginning to near the short-list for Pope, with Boston's Cardinal Sean O'Malley's having just been appointed to a Vatican advisory board.

Had he won, I could actually have claimed to have met the Pope. O'Malley was the bishop in Fall River when I converted to Catholicism in that city. As it happens, another bishop of my acquaintance is speaking at this year's conference: Providence Bishop Thomas Tobin is on the speaker's list.

Other speakers of whom readers of a conservative Web site should take note are George Weigel and Roger Kimball. Although I'm not as familiar with his work, I suspect Peter Steinfels will offer somewhat of a different perspective, as a former editor of Commonweal and religion correspondent for the New York Times. And of course, the musical performances and excellent meals propel the entire experience to otherworldliness.

Long-time readers of Anchor Rising will have seen my reports from previous years' conferences, but for a reminder or a sampling of what the conferences are like, take a look at our archives:

- 2009: "The Catholic William F. Buckley, Jr."

- 2010: "Newman and the Intellectual Tradition"

- 2011: "The Catholic Shakespeare?"

- 2012: "Modern Science, Ancient Faith"

It's amazing to think that this will be the fifth of these conferences. It's even more amazing to think of all that's happened in the world since they began. I recommend attending for a number of reasons, but perhaps the most profound is the much-needed perspective that the intellectual content and spiritual experience lends to the seemingly rapid and perilous pace of modern life.

March 31, 2013

If Spiritual Battles Gave Off Sparks

It’s been a while since I’ve seen it, so I had intended to watch The Passion of the Christ on Good Friday. But life’s being what it is, these days, I couldn’t manage the 126 minutes required. And by the time Saturday rolled around, it felt more appropriate to turn attention toward the Resurrection, which took up only about the final minute of the film.

So, at the end of an exhausting Holy Week of sick children and the consequent sleepless nights, my wife and I turned toward more explicit entertainment, with Christian messages mainly in its metaphors. We watched the first installment of The Hobbit.

The interplay of the thoughts about the two movies brought to mind an impression I took away from the Portsmouth Institute conference on Cardinal Newman in 2010: We have a habit of insisting that the reality of God ought to make the world something different from what it is, and then we blame Him for not making the world what it is not.

Either God exists within the world as we experience it, or He does not. Waiting for crosses burning the sky merely postpones the decision to believe, and as demonic faces in the explosion on September 11, 2001, proved, if you haven’t already decided, it would be awfully difficult for a supernatural sign to be decisive on its own.

More specifically, though, during the various speeches and presentations of the 2010 conference, I remember having the sense that the speakers were fundamentally talking about the reality of spiritual battle. Somehow, it seems, the modern imagination has atrophied in its capacity to believe in that which it cannot see.

With all of our gadgets and the nigh-upon-disprovable reality of video’s special effects, we need the light show. If a priest's counsel of a severely distraught person involved bolts of energy and explosions, few would doubt. If the long process of liberating people from possession by evil ideas came as wizards’ battle of wills and the revivification of the healed victim came with instant physical change, none would question the reality of the evil and the good.

In all respects, the ailment and the fact of being healed might be equivalent, but we look to the visible battle as the mark of reality. So, since we don’t experience magic in the world in the same way that we can imagine it in a movie, it seems all too plausible that nothing else that we can’t visibly see in life exists, either.

Further, in fiction we have no trouble placing the material in partnership with the spiritual, or the magic. Inadequate as swords may be against trolls, they offer some protection from the mystical. A robotic bird can be one wonder of many in a quest of gods and monsters.

Yet, in life, when human ingenuity gives us tools to fight the forces of evil and corruption, as well as the harmful vicissitudes of the world, as we learn how to manipulate chemicals to affect physiology and psychology, we conclude somehow that all must be material. I’d suggest that bombs and bullets can subdue military enemies, but performing the spiritual feat of changing people’s minds might be more powerful, still. Antidepressants may ease the sensation that unseen and down-pulling hooks are buried deep in every follicle, but imparting meaning and hope to each others' lives can be liberating without the drugs.

In that regard, the quick presentation of the Resurrection in The Passion carried the message well. Materially, we see a naked man in a tomb with a hole in his hand, stepping forward to martial music.

If we know the Bible, we know that, having returned from death, Jesus' main action was to have some conversations. There is some mention of the special effects, as it were, in His final appearances, but the miracle exists mainly in His appearance — that He’s among us.

We’ve celebrated Easter, yet again, and life will go on as it has. As for light shows and magic, I’m increasingly convinced that the decision is not one of determining what it means that they do not happen, but of observing that they do.

March 29, 2013

Fish on Fridays

Nothing symbolizes the supposed arbitrariness of religion to those predisposed towards skepticism towards religious belief more than does the Catholic practice of eating fish on Fridays during the season of Lent. I’ll admit to having asked myself, especially on Good Friday, what connection there is between fish and the crucifixion of Jesus Christ. And then there is the philosophical paradox. If my soul is lost after I’ve eaten meat on a Lenten Friday, does that mean I’m free to commit worse sins without making my situation worse? But if the rule doesn’t really matter, then why follow it? And on and on and on and on…

Here’s what I do know. With the choice of fish options available to a 21st century American, eating fish on Fridays is about as small a “sacrifice” in a material sense as can be asked for. But honoring the rule does require me to make some conscious choices that run contrary to what the surrounding culture tells me are cool and sensible. And if I am unable to make this small sacrifice, because I find it too inconvenient, or because I’m afraid to explain myself to others who don’t share my belief or who might think that I’m being just plain silly, then on what basis can I believe myself to be capable of taking a stand in more serious situations, when the choices might be a little harder and the stakes a bit higher?

Slightly edited re-post of an April 6, 2007 original.

November 30, 2012

Re: Keep Christ in Christmas, but the Government Out

I don't believe it's fair to blame WPRO (630AM) talk show host John DePetro for "manufacturing" the controversy about the Rhode Island Christmas tree/holiday tree.

The blame rests squarely with Governor Lincoln Chafee, who is claiming the authority to rename a religious symbol because he is the head of the state. (Bill O'Reilly is wrong when he says Christmas trees are a secular symbol).

To Governor Chafee and some of his extreme-liberal fellow travelers, it's just plain obvious that "separation of church and state" means that government has inherent authority to rename religious symbols. To other Rhode Islanders, many Rhode Islanders, the possession of such a power by government officials isn't a slam dunk.

When Governor Chafee tries explaining why government should involve itself with renaming religious symbols, he generally isn't very convincing and, as a result, often prefers to take the discussion towards declaring that there shouldn't be so much opposition to his decision because publicly voiced dissent, he believes, could create chaos. Or maybe dissent, on this issue, in the Governor's mind, is chaos.

These, in the end, are the two sources of the continuing Rhode Island Christmas tree controversy: a Governor who asserts that his office as head of state comes with the power to rename religious symbols and said Governor's intolerance for dissent from that position. That much public questioning occurs about the wisdom of both these propositions is not just acceptable but healthy.

September 29, 2012

The Messiah May Have Used the Word "Wife"

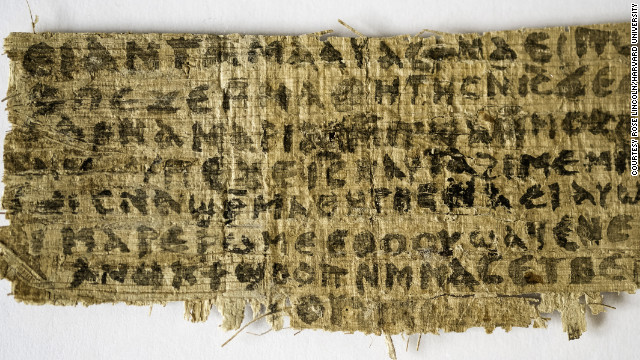

Of one thing, we can be reasonably confident: Coverage of proof and arguments against that sliver of papyrus purporting to prove that Jesus had a wife will have a far smaller profile than the initial boom of proclamations that it had been discovered.

Not surprisingly, the Vatican has stated its opinion that the artifact is "counterfeit," but what I found most interesting about the article is that it's the first time I've seen a picture of it:

I'll confess, off the bat, that I'm not able to read ancient Coptic text, but unless it's a remarkably compact language, that's really not much context on which to come to any conclusions. The paragraph before could have made clear that it was a parable. The paragraph to follow might have been an explanation of the Church's view that it (the Church) is the "bride of Christ." Or the whole thing might be some piece of nefarious propaganda.

I don't know, one way or the other, but the credulity with which such items are passed around is telling, especially with regard to the news media and the stories that it deigns to amplify.

September 20, 2012

Things We Read Today (15), Thursday

Issuing bonds to harm the housing market; disavowing movies in Pakistan and tearing down banners in Cranston; the Constitution as ours to protect; the quick failure of QE3; and Catholic social teaching as the bridge for the conservative-libertarian divide.

September 1, 2012

Rev. Rich Takes a Stand Against Small Children

Back when the Episcopal/Anglican Church was finding itself fraught with international internal turmoil over the appointment of an openly and actively homosexual bishop in New Hampshire, Catholic writer and blogger Mark Shea predicted, as an aphorism, that the organization would gradually turn toward the promotion of homosexuality. I always considered that a plausible, but not inevitable, course of the future.

After crossing an intellectual line, human organizations have a tendency to correct for excess, to transform into something unrecognizable, or to fade into non-existence. Shea's prediction was of the second category, but either of the other two (or even other variations of the middle one) remain possible for the Episcopal Church.

Rev. Timothy Rich, a relatively new rector at St. Luke's Episcopal Church in East Greenwich gives some evidence that Shea's prediction has certainly not been negated. Previously, it's interesting to note, Rich worked very closely with the aforementioned homosexual bishop, Eugene Robinson, as an assistant and Canon in New Hampshire.

During a summer in which Boy Scouts of America affirmed its policy of excluding "open and avowed homosexuals," Rev. Rich determined to investigate whether his church had any connection with the group. It turned out that a local Cub Scout pack — mainly boys aged six to eleven — uses the church for meetings.

The fifty boys involved are a bit young for the policy to have much effect, and Cub Master Jeff Lehoullier indicates that Pack 4 would do nothing to actively enforce the rule, even if it applied to pre-adolescent children. And who's to say but that by the time these actual flesh-and-blood children nearest Rich's flock reach the age of Eagle Scout, the organization won't have changed its view?

But Rich has some modicum of power, and he feels he must use it to "take a stand" against a national organization with which the church under his authority has a very limited, indirect relationship. That his action might have an adverse effect on dozens of the community's children — and that, by his action, he appears to be the one propagandizing a culture-war position beyond their ken — is a secondary consideration.

If radical rectors are to force a change in Boy Scout policy from the outside, thousands and thousands of children will have to be thus harmed and made to feel dirty and excluded by adults who ostensibly hold offices of respect in their community. Rich insists that, when it comes to the individual boys, he "support[s] them and applaud[s] their efforts," but apparently, when more than one of them gather together, they must be cast out and scorned.

No doubt, he's flattered by the media attention (his humble claims notwithstanding), and no doubt many people whose opinions he values highly have figuratively and literally slapped him on the back. The rest of us ought to question the motives and assumptions behind the movement of which he's made East Greenwich a part.

ADDENDUM:

I realize that a good portion of readers don't find discussion of scripture all that persuasive, but some further thought on this matter led me to an observation that definitely merits mention.

While reading comments on the East Greenwich Patch article on this issue, a phrase from the Bible came to mind: "Let the children come to me."

It's from Matthew 19, and the expanded passage is worth consideration.

Just before the disciples attempt to prevent the children from approaching Jesus, He has been explaining that the Old Testament permission to divorce should not apply to His followers because, "from the beginning the Creator 'made them male and female'... For this reason a man shall leave his father and mother and be joined to his wife, and the two shall become one flesh."

The disciples object that the teaching is so hard that "it is better not to marry." And Jesus suggests that some are "incapable" of marriage. Some translations of the Bible have Jesus referring to such people as "eunuchs."

Again, I realize that not everybody assigns spiritual weight to the Bible, but I would think that a Christian preacher would be inclined to do so. And this passage has many layers of profundity, all ultimately reinforcing a traditional view of marriage. The man and woman become "one flesh," and then the children come forward. Nobody should attempt to "separate" what God has joined, meaning the husband and wife, and then the disciples attempt to separate the children from Jesus, who in Catholic theology is the bridegroom of the Church.

In some practices, Episcopal theology differs substantially from Catholic, but it seems to me Rector Rich should contemplate this passage deeply, as should the members of his church.

July 11, 2012

Portsmouth Institute, Day 3: Rev. Nicanor Austriaco, "What Can Genomic Science Tell Us About Adam & Eve?"

The Portsmouth Institute conference on "Modern Science, Ancient Faith" closed in spectacular fashion with Rev. Nicanor Austriaco, who teaches both biology and theology at Providence College. With the ease and humor of somebody used to speaking before college students, Austriaco explained what genomic science tells us about our ancestors and speculated about the timing and historical environment of the common ancestors whom the Bible calls Adam and Eve.

In brief, Austriaco said that, mathematically, one would have to have had between 1,000 and 2,000 mating pairs 50,000 to 70,000 years ago in order for everybody alive today to have common ancestors and yet to be as diverse as we are. That is, Adam and Eve were not the only human beings (or matable humanoids) alive at the time, but they did something to displease God (I would say something having to do with the choice of self-awareness and related knowledge) that made them distinct, and their ancestral lines blended with others as time went on.

(That would certainly ease quite a bit of the discomfort with which the modern is likely to read the first few generations described in the Bible.)

He elaborated that anatomically modern human beings date back about 100,000-150,000 years, but behaviorally modern humans go back only 50,000.

During the question and answer portion (which ran beyond what the schedule had initially allowed), Austriaco spoke about original sin and its application to all of nature, not just the children of Adam and Eve. He referred back to Aquinas, suggesting that before the Fall, "eagles were eagles and lions were lions," but they killed in a somehow "ordered way," meaning with the proper alignment of things... material to spirit, man to God.

It doesn't take much effort to connect this thread with the idea articulated by William Dembski about two forms of information: one internal to nature and one entailing some form of creativity and intentionality. The information inside an acorn that leads it to "build" a tree can be seen as ordered; access to the disordered information that a material creature such as a human being applies to the creation of which he's a part fits very well with the Old Testament's description of events.

From there, one can see the accomplishment of Christ as being the reintroduction of the proper perspective for use of human beings' capacity for knowledge, with the emphasis on that which is outside of nature, in the same way that God is outside of His creation. The cross is the symbol of this proper alignment of material life and spiritual existence.

But as the various speakers at the conference illustrated by their own talks, one needn't go quite this far in order to see that science and religion can coexist, even as they press against each other along the uneven border between regions of human thought.

July 10, 2012

Portsmouth Institute, Day 2, Session 4: Dr. Michael Ruse, "Making Room for Faith in an Age of Science"

With a joke about philosophers and theologians (he being the former), Michael Ruse used the dinner speech of day two of the Portsmouth Institute conference on "Modern Science, Ancient Faith" to take up the ostensibly neutral (mutually skeptical) approach to arbitrating between religion and science.

He referred to both approaches to knowledge as "symbolic" — presenting metaphors to explain reality. For its part, science long ago became wedded to the metaphor of the universe as a machine. The human brain, for instance, is "a computer made out of meat." (That made me wonder whether they could be seen as accessing a spiritual Internet.)

Ultimately, he suggested, if your area of interest is investigating the clockworks of the world, then you're "just not talking about" things like ultimate causes, morality, and the point of it all. Of course (I'd interject), a great many people who see science and religion as opposed and incompatible insist that it can and should dabble in such philosophy.

Because they see science as potentially providing "ultimate causes," and they "worship chance" as Kevin O'Brien put it, in the character of Dom. Stanley Jaki, they do claim access to moral discernment. That, for instance, has been the core cause of push-back against evolution in the classroom. As misplaced as they may be, those religious believers aren't imagining that evolution as presented has given the faith of materialism a way around the otherwise iron-fisted separation of church and state.

July 9, 2012

Portsmouth Institute, Day 2, Session 3: Kevin O'Brien as Dom Stanley Jaki

At each of the Portsmouth Institute's conferences (except the first, as I recall), Kevin O'Brien of Theater of the Word has had some sort of performance. Last year, being on Catholicism and Shakespeare, his troupe performed scenes from Shakespeare with accompanying commentary.

O'Brien's other two performances, however, were self-composed biographical lectures given in the character of some notable religious figure. This year, it was Dom. Stanley Jaki, a priest who wrote voluminously on science.

As a performance art collection of various writings by Dom. Jaki, the talk stood as a collection of insights toward the broad statement of a particular case. Two related quotations illustrate well: "Science is the quantitative study of things in motion," which can lead to the fallacy that "what cannot be measured exactly cannot be exactly."

July 7, 2012

Portsmouth Institute, Day 2, Session 2: Dr. William Dembski, "An Informative-Theoretic Proof of God's Existence"

From an entertainment standpoint, the most interesting aspect of Bill Dembski's talk at the Portsmouth Institute conference on "Modern Science, Ancient Faith" was the continuation of what is apparently a long-standing head-to-head with the previous speaker, Ken Miller. Dembski is a notable personage on the intelligent design side of the public debate, and at one point issued a throw-down for a sort of public trial pitting Miller's crew against his own.

Most interesting from an intellectual standpoint, though, was Dembski's step away from the heat of a politically charged issue to his substantive argument with respect to evolution. In an echo of Miller's suggestion that organisms collect information from their environment, Dembski pointed out that "natural selection is a non-random search." How, then, did nature find that process?

Think of a time when you've done some tedious project. Eventually you may have come up with a process, or series of steps, that was more efficient than that with which you began. That took observation and analysis.

Dembski divided processes into two types of information. There is the information inside an acorn that tells it how to make a tree, and there is the information that a shipwright brings to bear when following a blueprint. Both forms of information exist, but only one is interior to nature and available for natural processes.

He told the story of an artist hired to make a bust of Beethoven. The client was none too impressed when the artist arrived with a large, untouched stone and explained that every particle of the Beethoven bust was inside the stone. Therefore, he had delivered exactly what he had promised.

I'd go a step farther with the analogy. What's critical about the fable is not that the artist didn't have a point; modern art is full of such gimmicks. The point is that the particular client did not like the statement made and, indeed, considered it to be a lazy scam. It's not just the material information contained in the particles of a statue, and it's not just the intellectual information contained in an artist's sketch (or even his too clever argument about the bust).

Rather, what we seek in art is that which speaks on another plane of existence: communication. The client did not like the message that he felt the artist had communicated.

This clearly, is the reemergence of the running, unspoken theme of the conference. That which makes suffering out of mere pain and beauty out of mere material coincidence is communication and the conscious sense thereof. Slippery and prone to misinterpretation as it may be, it is as real as the subatomic particles in our atoms and indicates an abstract space outside of the material universe.

July 5, 2012

Portsmouth Institute, Day 2, Session 1: Dr. Kenneth Miller, "To Find God in All Things"

Brown University biology professor Ken Miller opened the second day of conferences at this year's Portsmouth Institute conference, "Modern Science, Ancient Faith." Readers may find his name familiar, inasmuch as he was a central figure when the teaching of evolution was big news a few years back. He also stood out, among the academics for evolution in that he remains a practicing Catholic and does not present evolution as counter-evidential to God.

As a professor and one who has spoken on the topic many times, Miller's presentation was very enjoyable, and he handily won over the audience. Of course, it was clear from the beginning of the conference, that the audience was far from creationist in its general viewpoint. It is descriptive, rather than derogatory, to say that one would expect such a view from educated Catholics.

That said, Miller still had the pique of the heated public debate days, as evident in his insistence that the decisions of a school district in Pennsylvania was nearly an existential battle over "the place of scientific inquiry itself." That may be true, if one believes that scientific inquiry ought to be the pole star of all society, without variation across the vast landscape of the United States, but conservatives (at least) ought to worry about the implications of dictating even that.

Surely, in the mix of considerations that society must integrate for the health and happiness of its members, other principles can be higher than scientific inquiry. That, one can't help but feel, explains some of the uneasiness even among evolutionist believers with the terms of the evolution versus intelligent design debate (and has a familiar feel, the day after Independence Day). Perhaps there are higher ideals that supersede the narrow debate about evolution, just as God supersedes the observable natural process itself.

Most significant, though, was Miller's tacit continuation of the theme that underlay the entire conference, manifesting in two points that he made. Describing the relatively rapid evolution of bacteria in the lab to be able to break down a pesticide, he explained that "living organisms harvest information from the environment." One could pivot on the point (and the experiment) to note that shaping the environment is precisely a tool for designing life, but it's the idea of information that leads toward new discussion, as opposed to returning to the battles of the past.

The second appearance of the theme arose when Miller highlighted fire rainbows as so beautiful as to constitute a religious experience, yet entirely explicable through the material processes. As with John Haught's reference to suffering, though there appear to be two types of information in play: one involving the instructions within nature about how material things must respond to their environment, and one involving a higher perspective of conscious subjectivity.

The former explains ice crystals' treatment of light and a living organisms reaction to painful sensations. The latter is what elevates pain to suffering and refraction to beauty.

July 4, 2012

Portsmouth Institute, Day 1, Session 3: Dr. John Haught, "Evolution and Faith: What Is the Problem?"

Georgetown University theology professor John Haught firmly established the theme of the Portsmouth Institute conference on "Modern Science, Ancient Faith" with his talk on the reconciliation of religion and science — even if he arguably did so without explicitly stating it.

Dr. Haught did so by taking up several of the philosophical objections to Christian theology, where it touches on the observable world. How, one question asks, could a good God have created a world with so much suffering?

Haught's entire presentation was in some ways an answer, but one of the key concepts that he offered was that life has a "narrative character"; it's a story, which is after all the "medium of meaning." He asked, rhetorically, "Would you try to make the world nice and safe?" Beginning a world with that requirement would sure produce a different outcome, but by many human measures (and probably most divine measures) it would be inferior.

Another rhetorical question that Haught poses inspired his most memorable image: If the point of the universe was intelligent life, why did it take so long? To illustrate argument, he showed a picture of 30 books of 450 pages each. Human life would appear on the very last page of the very last volume.

His answer was that the universe is in the process of becoming "something other than God in creation." We're experiencing that process..

One might also inquire of the rhetorical asker (somewhat whimsically) how long he could play in the sandbox of the universe, with full view of the tiniest particle and the largest galaxy, before interest demanded a new features, like life. But the idea at the next intellectual step after Haught's argument is much more satisfactory: As a Being in some sense beyond creation, God may be considered outside of time, as well as material. That being the case, creation was instantaneous from His perspective; we're just within it as it unfolds.

The idea of God — of spirit — beyond the material universe also provides answer to the argument about suffering, as would come into focus as the conference proceeded the next day.

ADDENDUM:

This paragraph, from a New York Times article about the official "discovery" of the Higgs boson, seems supremely relevant to the above:

Confirmation of the Higgs boson or something very like it would constitute a rendezvous with destiny for a generation of physicists who have believed in the boson for half a century without ever seeing it. And it reaffirms a grand view of a universe ruled by simple and elegant and symmetrical laws, but in which everything interesting in it, such as ourselves, is due to flaws or breaks in that symmetry.

July 3, 2012

Portsmouth Institute, Day 1, Session 2: Abbott James Wiseman, "A New Heaven and a New Earth"

Among the truly fascinating aspects of the entire 2012 Portsmouth Institute conference, "Modern Science, Ancient Faith," was the pervasive appearance of an underlying theme. That, in itself, is not surprising; the fact that nobody took its appearance as opportunity actually to state it is.

In retrospect, in the second lecture of the series, Brother Wiseman was most explicit on the point. His talk had much to do with the proper relationship of science and religion and the translation of revelation into terms consistent with the material world. Revelation, as he said, does not give exact knowledge of the world, present or future, but rather a sense of how things are and ought to be.

Of particular interest was the time that Wiseman spent on eschatology, or the religious expectation of the end of this world. In this regard, he spoke of past theologians who held that we could not separate the material and the spirit in our hope for "a state beyond decay and suffering." Indeed, and here's the hint of that which grew to be fascinating later, he spoke of the end days as a "conversion of energy into pure information."

It appears that the theologians were conspicuously reluctant to translate that vision into concrete predictions, but when combined with the notion — expressed by Wiseman and repeated throughout the weekend — that one must look beyond science for a full explanation of reality, it begins to transform into a workable model for ultimate questions.

July 2, 2012

Portsmouth Institute, Day 1, Session 1: Dom Paschal Scotti, "Galileo Revisited"

It was fitting that the the 2012 Portsmouth Institute conference, "Modern Science, Ancient Faith," held at the Portsmouth Abbey school, opened on the topic of Galileo.

Brother Scotti addressed the ways in which other factors brought about the Catholic Church's blunder with respect to Galileo. There were internal politics. Factional rifts between the Jesuits, who were more friendly to Galileo, and the Dominicans. Personality conflicts and ego-driven attacks, including on the part of the "academic superstar" scientist himself.

The bottom line, however, as Scotti told an audience member after the speech, is that the Church has actually done very well with respect to integrating science into its worldview and presentation. But when it got things wrong, with Galileo, it got them spectacularly wrong.

One particularly interesting point arose when an audience member asked whether our intelligence has arguably returned mankind to status as the center of the universe. Scotti replied that, in the old Ptolemaic view, Earth wasn't the pinnacle of the universe, but "the lowest place, the worst place," the place to which frailty sank.

May 14, 2012

Science and Religion Winding Through a Summer's Day

According to the Chinese calendar, 2012 is another year of the dragon. By the cyclical calendar of the United States, it's another year of the campaign, and early indications are that it will be a fierce one. No doubt, when the post-election chill deadens the flames this winter, we'll all be very relieved to see it over.

Already, we news consumers have been treated to institutionalized schoolyard taunts. Apparently, as a young father, Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney built a shielded crate for his dog, to transport the pooch on top of the family car. President Barack Obama, for his part, dined on canine meat as a boy. We can be assured that these automotive and culinary anecdotes are a mere foretaste of the potluck fare to which we'll be treated as the months advance.

Whatever the personal aftertastes with which voters are left, few can doubt that ballots will be cast with larger matters in mind. The economy loiters in the neighborhood between stagnation and depression. As a matter of political philosophy, secular healthcare advocates mix shouts across the intersection of human rights with those espousing freedoms of conscience. Such are the substantive topics of our day.

Still, history may show even these battles to be the seasonal oscillations of a society too comfortable that existential questions have either been answered or are immaterial. Even as we have heated debates about whether elite law-school students ought to have to pay for their own contraception, the expanding capacity of science to do is making ever more immediate the discussion about whether to do.

It will, therefore, be a welcome diversion into weightier matters to attend the Portsmouth Institute's conference addressing "Modern Science/Ancient Faith" in the waning days of June. Every summer for the past three, the institute has hosted speakers and audiences on the campus of the Portsmouth Abbey School, but this is the first that centers around a topic rather than a personality.

As its first election-year event, too, the institute experience will contrast all the more with the rancor of daily life. While in the midst of such decisions as drive us haphazardly through each day, the notion that we can choose what air to breathe feels frivolous, and that is what a brief pause for intellectual pursuits is like. Away from the challenges of making a living is the space to consider subtle ideas with the gravity that they deserve.

The topic of the year illustrates the point very well. How we individually balance science and faith (consciously or implicitly) will affect how we choose to live. It is not irrelevant. It should not, moreover, be a mere marker of our philosophical tribe or political party.

Yet, that is what we tend to do. It is the Sciencers versus the Faithers, like warring gangs in dancing knife duels. Pick a side.

The other option is the passive version of the same tendency: dismissing the debate as an attempt to pit apples versus oranges when no overlap should be acknowledged. The error, here, is in failing to see that science and religion really do collide, at least in their practical application in the hands of human beings.

Despite its many innovations, science has not freed humanity from our inclination toward bias, in particular the bias for one's own will imposed upon another. Just as those who've abused people's natural religious impulses have sold their own personal interests as God's will, "the science shows" can be a key phrase in the demagogue's arsenal.

It is to the benefit of such would-be demagogues to place excessive emphasis on the "ancient" in "ancient faith." Thus, they give the impression that religion, particular religious doctrines, emerged once, long ago, in perfectly expressed fashion. In this view, if the Bible, for one, applies only obliquely to a modern situation, it must therefore be a fad of the past.

A faith frozen in its state millennia ago is juxtaposed with a fresh new science, full of modern comprehension of the world around us. It would be more true to suggest that what is ancient, in religion, is the framework around which we've ever since draped human experience, giving form to a reality that we are too limited in our vision to see.

The dragons winding their way through Chinese New Year parades have evolved in the materials used to create them. Their form remains largely the same, however.

Their import, well, that's another matter, as is the appropriate balance of technology and tradition — one that is well worth considering for an enjoyable few days in June, in the terms of science and religion.

April 6, 2012

Fish on Fridays

Nothing symbolizes the supposed arbitrariness of religion to those predisposed towards skepticism towards religious belief more than does the Catholic practice of eating fish on Fridays during the season of Lent. I’ll admit to having asked myself, especially on Good Friday, what connection there is between fish and the crucifixion of Jesus Christ. And then there is the philosophical paradox. If my soul is lost after I’ve eaten meat on a Lenten Friday, does that mean I’m free to commit worse sins without making my situation worse? But if the rule doesn’t really matter, then why follow it? And on and on and on and on…

Here’s what I do know. With the choice of fish options available to a 21st century American, eating fish on Fridays is about as small a “sacrifice” in a material sense as can be asked for. But honoring the rule does require me to make some conscious choices that run contrary to what the surrounding culture tells me are cool and sensible. And if I am unable to make this small sacrifice, because I find it too inconvenient, or because I’m afraid to explain myself to others who don’t share my belief or who might think that I’m being just plain silly, then on what basis can I believe myself to be capable of taking a stand in more serious situations, when the choices might be a little harder and the stakes a bit higher?

Slightly edited re-post of an April 6, 2007 original.

February 13, 2012

Rahe: Catholic Church Reaping What it Helped Sow

With the ongoing controversy between the Obama Administration and religious institutions--particularly the Catholic Church--as to whether the health care plans offered by the institutions should cover items they deem inconsistent with their religious tenets (ie; contraception, etc.), Paul Rahe writes that the support given to various progressive causes by the institution of the Catholic Church, in particular, has come back to bite them. He provides some history:

In the 1930s, the majority of the bishops, priests, and nuns sold their souls to the devil, and they did so with the best of intentions. In their concern for the suffering of those out of work and destitute, they wholeheartedly embraced the New Deal. They gloried in the fact that Franklin Delano Roosevelt made Frances Perkins – a devout Anglo-Catholic laywoman who belonged to the Episcopalian Church but retreated on occasion to a Catholic convent – Secretary of Labor and the first member of her sex to be awarded a cabinet post. And they welcomed Social Security – which was her handiwork. They did not stop to ponder whether public provision in this regard would subvert the moral principle that children are responsible for the well-being of their parents. They did not stop to consider whether this measure would reduce the incentives for procreation and nourish the temptation to think of sexual intercourse as an indoor sport. They did not stop to think.He also offers anecdotal evidence:In the process, the leaders of the American Catholic Church fell prey to a conceit that had long before ensnared a great many mainstream Protestants in the United States – the notion that public provision is somehow akin to charity – and so they fostered state paternalism and undermined what they professed to teach: that charity is an individual responsibility and that it is appropriate that the laity join together under the leadership of the Church to alleviate the suffering of the poor. In its place, they helped establish the Machiavellian principle that underpins modern liberalism – the notion that it is our Christian duty to confiscate other people’s money and redistribute it.

At every turn in American politics since that time, you will find the hierarchy assisting the Democratic Party and promoting the growth of the administrative entitlements state. At no point have its members evidenced any concern for sustaining limited government and protecting the rights of individuals. It did not cross the minds of these prelates that the liberty of conscience which they had grown to cherish is part of a larger package – that the paternalistic state, which recognizes no legitimate limits on its power and scope, that they had embraced would someday turn on the Church and seek to dictate whom it chose to teach its doctrines and how, more generally, it would conduct its affairs.

I would submit that the bishops, nuns, and priests now screaming bloody murder have gotten what they asked for. The weapon that Barack Obama has directed at the Church was fashioned to a considerable degree by Catholic churchmen. They welcomed Obamacare. They encouraged Senators and Congressmen who professed to be Catholics to vote for it. {Emphasis added.}

I was reared a Catholic, wandered out of the Church, and stumbled back in more than thirteen years ago. I have been a regular attendee at mass since that time. I travel a great deal and frequently find myself in a diocese not my own. In these years, I have heard sermons articulating the case against abortion thrice – once in Louisiana at a mass said by the retired Archbishop there; once at the cathedral in Tulsa, Oklahoma; and two weeks ago in our parish in Hillsdale, Michigan. The truth is that the priests in the United States are far more likely to push the “social justice” agenda of the Church from the pulpit than to instruct the faithful in the evils of abortion.Rahe goes into much greater depth than these snippets indicate and it's worth a read (whether you tend to agree or disagree).And there is more. I have not once in those years heard the argument against contraception articulated from the pulpit, and I have not once heard the argument for chastity articulated. In the face of the sexual revolution, the bishops priests, and nuns of the American Church have by and large fallen silent. In effect, they have abandoned the moral teaching of the Roman Catholic Church in order to articulate a defense of the administrative entitlements state and its progressive expansion.

February 10, 2012

Memo to Bishops: Don't Fall For It

The Washington Post has collected a spectrum of religious reactions to the Obama administration's "compromise" — apparently announced as such without first consulting with the parties implicitly involved in the negotiations (a sure sign that Obama is more concerned about appearing to compromise than actually doing so). Religious leaders and others concerned about religious liberty — in particular those concerned about our ability to work through cultural avenues distinct from government to help shape society — should pause in their deliberations about the specifics of this overture.

Note what position the President's games put us in: We're not arguing about the morality of contraception (including abortifacients). We're not even arguing about the legitimacy of the government's declaration that everybody should have access to them free of cost (at least free of immediate cost to them). We're merely arguing about who else must pay — who has to chip in for the pills that address pregnancy as an illness to be treated and against which to be inoculated.

One hopes that the administration's initial overreach was enough to awaken the bishops and others to the reality that a deal with the Devil is always, always conditional on his ability to force you to the next-least-moral space on the playing field.

January 25, 2012

The Cranston West Banner and State Inhibition of Religion

Folks who invoke ideas like the “the enduring legacy of Roger Williams” as a means for deciding contemporary policy issues such as Steve Ahlquist of the Humanists of Rhode Island, continue to be confused about what that legacy actually entails. A Saturday Projo op-ed by Mr. Ahlquist from which the above quoted phrase was taken, claims that…

…Williams worked to establish a government in Rhode Island that guaranteed [freedom of conscience and freedom of religion] by helping to draft a charter for the colony that was unique in the world because it contained no mention of God.This is not true, as Marc pointed out earlier this year. Rhode Island’s colonial charter, famous for its guarantee of freedom of conscience “in matters of religious concernments”, mentions God and the Gospels, in more than just a milquetoast fashion…

[T]hat true piety rightly grounded upon gospel principles, will give the best and greatest security to sovereignty…Surprisingly (to some) religious freedom and God can actually complement one another.They may win and invite the native Indians of the country to the knowledge and obedience of the only true God, and Saviour of mankind…

Roger Williams directly expressed his own thoughts on the duties "public magistrates" had with respect to a religion that they “believeth to be true” in “The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution” published in 1644. One such duty towards religion was…

Approbation and countenance, a reverent esteem and honorable testimony, according to Isa. 49, and Revel. 21, with a tender respect of truth, and the professors of it.The Bloudy Tenent also lists five “proper means” of civil government, the second of the five being…

The making, publishing, and establishing of wholesome civil laws, not only such as concern civil justice, but also the free passage of true religion; for outward civil peace ariseth and is maintained from them both.A blanket ban on mention of God in government-controlled spaces does not automatically align with “the free passage of true religion” that Williams thought was a legitimate concern of civil government, nor allow opportunities for the “reverent esteem and honorable testimony” for religion that he favored.

Now, despite ample room in Roger Williams' vision of church-state relations for hoisting a banner addressing Our Heavenly Father, Williams' views are not and should not be the only factor that decides the resolution of the issue today. However, Williams' belief that the civil government had a role in “the free passage of true religion” has propagated forward, formally at least, to become part of the test that the Supreme Court has created for determining the acceptability of religious displays on public property (the "Lemon test", named for the case of Lemon v. Kurtzman). The relevant prong is the second one …

First, the statute must have a secular legislative purpose; second, its principal or primary effect must be one that neither advances nor inhibits religion; finally, the statute must not foster "an excessive government entanglement with religion."Tests for government not advancing religion have been enforced through the court’s construction of a “reasonable observer” who possesses rabbit ears where mention of God or religion is involved. Concern for the no-inhibiting prong of the test has been considerably less vigilant.

* * *

Suppose that the Cranston West Banner was addressed to someone other than a Heavenly Father. Here’s one possibility…Mother Gaia,This might not pass the Lemon test – an anthropomorphic Mother Gaia might offend the courts’ tastes. On the other hand, the basic concept could probably be made acceptable by turning Mother Gaia into something a little more concrete...

Grant us each day the desire to do our best...

All-encompassing ecosystem of the earth,You also could come up with a version that skips the druidic sentiment and emphasizes collective humanity instead, something like Jean-Jacques Rousseau might write...

Grant us each day the desire to do our best...

Indestructible and infallible General Will of the community,…or that a Marxist might write…

Grant us each day the desire to do our best...

True consciousness of the proletariat,…and by pressing the Marxist envelope a little further, you could even get rid of people entirely, and ask for help only from the inanimate…

Grant us each day the desire to do our best...

Dialectic, impersonal and material forces of production,There’s certainly nothing spiritual in that last one that would trigger a Lemon Alert.

Grant us each day the desire to do our best...

But this list of what is versus what isn’t acceptable under the Lemon Test presents a problem. A wide definition of what “advances” religion per one part of the Lemon test has led to almost total neglect of the prohibition against "inhibiting" religion in another. A message displayed in a publicly-managed space asking for help from God in leading a better life is deemed unacceptable, while the same request in the same place made to the highest power that exists in the minds of Marxists, Romantics, naturalists, humanists, or shut-up-and-obey-the-statists would probably be OK. Religion has been inhibited by official state sanction -- officially deemed by the state to be somehow less worthy of free expression than other belief systems -- in a way that the Lemon test supposedly prevents.

Working from the state of the law and of society now, wherever the state bans the mention of God as an acceptable answer to the big questions, the state must also allow opportunities make clear that it is not allowed to take the position that God is less of an answer than other answers that are possible. This can be done at the present moment in the City of Cranston with a modification to the banner that respects the local history of the issue and the larger religious and philosophical questions involved, and that is consistent with the Lemon test and with the tradition of Roger Williams…

In 1963, David Bradley and the Cranston West community chose the imperative mood, to express a message they believed would help the members of the community live and grow together.In 2012, Judge Ronald Lagueux ruled that the state forbids mentioning to whom or to what the requests are addressed.

Judge Lagueux's ruling should not prevent anyone's lifelong consideration of all of the reasons why we aspire to be better on our next day than on our last,

nor imply that the state can decide the answer to this question for us.

*** ******** *******

Grant us each day the desire to do our best,

To grow mentally and morally as well as physically,

To be kind and helpful to our classmates and teachers,

To be honest with ourselves as well as with others,

Help us to be good sports and smile when we lose as well as when we win,

Teach us the value of true friendship,

Help us always to conduct ourselves so as to bring credit to Cranston

High School West.

****

January 17, 2012

The Cranston West Banner Can't be Required to Just Disappear

If the Cranston West banner has to be destroyed or removed, or if certain words have to be redacted from it, to comply with Judge Ronald Lagueux's Federal Court decision, there is no reason why a Soviet-style disappearance from history without explanation must occur, or that the public should not be informed that they are looking at a version 2 of the banner or at the space where the banner used to be.

If the minimum-modification option is pursued, various utilizations of the space on top or to the side of the banner are possible for displaying an explanation that would respect the history and original message of the banner, without violating any Supreme Court "endorsement of religion" tests.

Here's one proposal...

In 1963, David Bradley and the Cranston West community chose the imperative mood, to express a message they believed would help people live and grow together.In the meantime, a note should be added to the tarp covering the present banner saying "The Federal Government forbids you from seeing what is behind this covering".In 2012, Judge Ronald Lagueux ruled that the state forbids mentioning to whom or to what the requests are addressed.

Judge Lagueux's ruling should not prevent anyone's lifelong consideration of all of the reasons why we aspire to be better on our next day than on our last,

nor imply that the state can decide the answer to this question for us.

*** ******** *******

Grant us each day the desire to do our best,

To grow mentally and morally as well as physically,

To be kind and helpful to our classmates and teachers,

To be honest with ourselves as well as with others,

Help us to be good sports and smile when we lose as well as when we win,

Teach us the value of true friendship,

Help us always to conduct ourselves so as to bring credit to Cranston

High School West.

****

December 5, 2011

Yes, Reverend, What We Call It Matters

The annual battle over Christmas terminology isn't a sport for which I have much enthusiasm, the lines having been drawn and a general consensus reached. As a matter of governance, I think that local governments ought to be able to reflect the makeup of their communities, if that's what the folks who live there want, and that deliberately running from a religious reference is tantamount to unconstitutional expression of governmental religious preference. But this is ground that's been covered over and over.

It is telling that Governor Lincoln Chafee couldn't even muster a nod, as governor, to his ideological opponents and, acknowledging the General Assembly's action early in the year asking public officials to refer to such decorations as "Christmas trees," do so as a symbolic gesture of respect and concession. In Chafee, we find an ideologue who thinks sticking to his guns makes him a centrist.

More interesting, in my view, are the thoughts of Executive Minister of the Rhode Island State Council of Churches Rev. Don Anderson:

I would ask my fellow Christians, with all of the poverty, hunger and injustice that surround us, do we really believe that Jesus would have us spend all this time and energy around what we call a tree? I would suggest that if we truly want to honor the birth of Jesus, let us be found honoring and serving one another in recognition and thanksgiving for what God has done for us.

What Anderson elides is that Jesus' mission wasn't merely one of social work, but also of conversion. Recall the anointing at Bethany:

... a woman came up to him with an alabaster jar of costly perfumed oil, and poured it on his head while he was reclining at table. When the disciples saw this, they were indignant and said, "Why this waste? It could have been sold for much, and the money given to the poor."Since Jesus knew this, he said to them, "Why do you make trouble for the woman? She has done a good thing for me. The poor you will always have with you; but you will not always have me.

Immediately thereafter, in the book of Matthew, Judas agrees to betray Jesus — although whether in reaction to His dalliance in material pleasure or with the understanding that he is helping to fulfill Jesus' plan makes for an interesting theological debate. More relevant to the current controversy, however, is the simple fact of Jesus' statement that His bodily presence supersedes in importance the existence of material poverty.

Above everything, in the Christian interpretation, Jesus gave a face to God, as a model and guide. Throughout the Gospels, Jesus intermixes the admonition to do good for others as a way of doing good for Him with the command to spread His Word so that others will do the same. That is, why Christians have good will toward men is as important as that they do.

Happily, most people still understand (for the time being, at least) that a "holiday tree" is really a "Christmas tree," and related to a holiday celebrating the birth of the Messiah who taught these lessons, so little is lost by not naming the holiday at a tree lighting. (Of course, euphemism can be a species of dishonesty.) But Anderson's dismissal of the issue strikes me as a reckless exercise in political correctness that, if taken to the extreme that it often is, will ultimately undermine both the recognition of Christ and His explanation for the commandment to help others.

Ross Douthat expressed an applicable sentiment in a print National Review essay about the (mostly secular) pilgrimage movie, The Way:

In reality, religion — and more particularly, Catholicism — has everything to do with why The Way packs both an artistic and a metaphysical punch. Both the aesthetic and the spiritual realms thrive on specificity: on iconography that refers to something in particular, on moral frameworks that provide guidance for hard cases as well as general admonitions. Without these specifics, there would be no Santiago de Compostela, no Camino for the doubting modern pilgrims of The Way to walk, no sins to be forgiven, and no one to offer absolution.

After all, if the inspiration for decorating a tree is of no consequence, the inspiration for building magnificent churches must be as well, and so too the inspiration for making of our lives shrines to the God whom we are to see in the faces of our fellow men and women. Simply doing good deeds may be adequate for a generation or two, but eventually, people will forget the true names of the symbols and the explanation for their good behavior. God's voice will remain in us, calling through our consciences, but if that is enough, then why did He send his Son on Christmas Day only to be killed on Good Friday?

October 24, 2011

The Catholic Notion of a Global Authority

It comes around once a year in the missal for the Catholic Mass, and the lector, standing before his or her neighbors to read the holy words very often exudes a palpable discomfort:

Be subordinate to one another out of reverence for Christ.

Wives should be subordinate to their husbands as to the Lord.

For the husband is head of his wife just as Christ is head of the church, he himself the savior of the body.

As the church is subordinate to Christ, so wives should be subordinate to their husbands in everything.

Husbands, love your wives, even as Christ loved the church and handed himself over for her to sanctify her, cleansing her by the bath of water with the word, that he might present to himself the church in splendor, without spot or wrinkle or any such thing, that she might be holy and without blemish.

So [also] husbands should love their wives as their own bodies. He who loves his wife loves himself.

It's the second line in this passage from St. Paul's letter to the Ephesians that sticks in modern throats. Subordinate? I think not. What's missed is the balance between the calls to each spouse. The subordination requested is to a man who would do as Christ did and die a horrible death for those He loves. The dutiful husband and father is to be a savior to his family after the model of a crucified Christ. It's subordination to a man who is called to be subordinate right back. She realizes that she is part of him, and he realizes that she is him.

Something similar is at play in the typically unnuanced MSM characterization of the Vatican's new document, "Note on financial reform from the Pontifical Council for Justice and peace."

The Vatican called on Monday for the establishment of a "global public authority" and a "central world bank" to rule over financial institutions that have become outdated and often ineffective in dealing fairly with crises. The document from the Vatican's Justice and Peace department should please the "Occupy Wall Street" demonstrators and similar movements around the world who have protested against the economic downturn. "Towards Reforming the International Financial and Monetary Systems in the Context of a Global Public Authority," was at times very specific, calling, for example, for taxation measures on financial transactions. ... It condemned what it called "the idolatry of the market" as well as a "neo-liberal thinking" that it said looked exclusively at technical solutions to economic problems. "In fact, the crisis has revealed behaviours like selfishness, collective greed and hoarding of goods on a great scale," it said, adding that world economics needed an "ethic of solidarity" among rich and poor nations. ... It called for the establishment of "a supranational authority" with worldwide scope and "universal jurisdiction" to guide economic policies and decisions.

The Vatican didn't "call for the establishment" of such an authority in the sense that the world's leaders ought to get to work on it tomorrow. Rather, the document describes a long evolution toward an ideal. And as with St. Paul's characterization of marriage, the document isn't as one-sidedly anti-free-market as Philip Pullella's Reuters summary, above, suggests. It also acknowledges the risks of socialism and technocracy. Consider:

However, to interpret the current new social question lucidly, we must avoid the error — itself a product of neo-liberal thinking — that would consider all the problems that need tackling to be exclusively of a technical nature. In such a guise, they evade the needed discernment and ethical evaluation. In this context Benedict XVI's encyclical warns about the dangers of the technocracy ideology: that is, of making technology absolute, which "tends to prevent people from recognizing anything that cannot be explained in terms of matter alone" and minimizing the value of the choices made by the concrete human individual who works in the economic-financial system by reducing them to mere technical variables. Being closed to a "beyond" in the sense of something more than technology, not only makes it impossible to find adequate solutions to the problems, but it impoverishes the principal victims of the crisis more and more from the material standpoint.In the context of the complexity of the phenomena, the importance of the ethical and cultural factors cannot be overlooked or underestimated. In fact, the crisis has revealed behaviours like selfishness, collective greed and the hoarding of goods on a great scale. No one can be content with seeing man live like "a wolf to his fellow man", according to the concept expounded by Hobbes. No one can in conscience accept the development of some countries to the detriment of others. If no solutions are found to the various forms of injustice, the negative effects that will follow on the social, political and economic level will be destined to create a climate of growing hostility and even violence, and ultimately undermine the very foundations of democratic institutions, even the ones considered most solid.

Recognizing the primacy of being over having and of ethics over the economy, the world's peoples ought to adopt an ethic of solidarity as the animating core of their action. This implies abandoning all forms of petty selfishness and embracing the logic of the global common good which transcends merely contingent, particular interests. In a word, they ought to have a keen sense of belonging to the human family which means sharing the common dignity of all human beings: "Even prior to the logic of a fair exchange of goods and the forms of justice appropriate to it, there exists something which is due to man because he is man, by reason of his lofty dignity."

In 1991, after the failure of Marxist communism, Blessed John Paul II had already warned of the risk of an "idolatry of the market, an idolatry which ignores the existence of goods which by their nature are not and cannot be mere commodities." Today his warning needs to be heeded without delay and a road must be taken that is in greater harmony with the dignity and transcendent vocation of the person and the human family.

I will certainly not be the last to acknowledge that religious people are just as prone as anybody to muddled economic thinking, and those who hew their careers and behavior most closely to the premise that a higher authority has a claim on their lives are no less prone to err in their trust of human authority than those who believe human beings can control everything. But what this particular document is describing is a human development that brings the people of the world together toward common advancement with full respect of individual autonomy.

That objective is, or ought to be, not only consistent with, but inherent to any ethical approach to economic liberty. The libertarian ideal, in other words, shouldn't be "let me do whatever I want," but rather, "let me do good in the way that I think best." And the global authority here described is one that conveys feedback in a deeper manner than achieved by price systems. Otherwise, the Vatican is warning, a prosperous peace cannot continue.

To lash out at suggestions of global cooperation is to miss the opportunity presented by such statements as this, from the Vatican's document (emphasis added):

... It is a matter of an Authority with a global reach that cannot be imposed by force, coercion or violence, but should be the outcome of a free and shared agreement and a reflection of the permanent and historic needs of the world common good. It ought to arise from a process of progressive maturation of consciences and freedoms as well as the awareness of growing responsibilities. Consequently, reciprocal trust, autonomy and participation cannot be overlooked as if they were superfluous elements. ...As we read in Caritas in Veritate, "The governance of globalization must be marked by subsidiarity, articulated into several layers and involving different levels that can work together." Only in this way can the danger of a central Authority's bureaucratic isolation be avoided, which would otherwise risk being delegitimized by an excessive distance from the realities on which it is based and easily fall prey to paternalistic, technocratic or hegemonic temptations. ...

These measures ought to be conceived of as some of the first steps in view of a public Authority with universal jurisdiction; as a first stage in a longer effort by the global community to steer its institutions towards achieving the common good. Other stages will have to follow in which the dynamics familiar to us may become more marked, but they may also be accompanied by changes which would be useless to try to predict today.

Clearly, this is not a Cato Institute policy paper, but at the same time, it allows the room to suggest that the "changes" that we cannot predict include the development of social institutions outside of government — institutions of mutual consent and understanding, but consistent with free will and personal autonomy — that provide the necessary authority for consensual cooperation.

The error in the typical reaction to this sort of application of Catholic theology to the material world is to imagine that the Church has seen the future and it is the EU and UN writ large. Beneath the jargon of social justice writing is actually a call to re-imagine what global authority might look like, and it is a project that free-marketers ought to undertake with as much zeal as those who can think of nothing more original than the repackaged Marxism, which this very document describes as a failure.

June 21, 2011

Portsmouth Institute, "The Catholic Shakespeare?," Sunday, June 12

This year's Portsmouth Institute conference changed things up a bit by eliminating the one or two presentations from Thursday and lining up three for Sunday. It definitely made sense to better utilize the second weekend day, although the talks came in such rapid succession that a second viewing with time to ruminate is in order.

The speakers each took up a different play and offered some suggestion about their basis and meaning. First, Dr. Gerard Kilroy, of University College, London, assembled linguistic and thematic cues to suggest Romeo and Juliet as an allegory for believers and the Catholic Church, respectively:

The next speaker, Dennis Taylor, took a more historical approach in his review of Shakespeare's play The Tempest, tracing Catholic links to early efforts to explore the Americas. Apparently, some of the initial ventures in that effort carried with them the prospects of founding a refuge for English Catholics.

Closing out the day and the conference, Fr. David Beauregard took a religious and philosophical look at relationships, charity, and the development of virtue in The Tempest. (I apologize for the technical lapse in the middle of the speech.)

As always, I left the Portsmouth Abbey campus with a bit of melancholy that my annual taste of a more refined and intellectual life had come to a close. Was Shakespeare Catholic? Well, he was certainly sympathetic to Catholics' plight and had personal connections to people who were persecuted for their faith. Moreover, in the artist's quest for the profound, the tremendous religious turmoil of his day would have been a ready well.

With such venues and events as presented by the Portsmouth Institute, one can draw a sip and begin to see the deeper threads through the human experience, into our own day. Whatever the topic when next year comes around, it is always regenerative to find that the complications and labors of passing life are not all.

June 17, 2011

Portsmouth Institute, "The Catholic Shakespeare?," Saturday, June 11

The Saturday sessions of the Portsmouth Institute's conference, this year, began with Clare Asquith, speaking on "As You Like It and the Elizabethan Catholic Dilemma":

Mrs. Asquith's acute thesis is that Shakespeare wrote the play with a particular Catholic family in mind — indeed, perhaps under that family's patronage. Her broader suggestion is that the religious atmosphere of the time couldn't help but permeate the plays. For one thing, the various religious identity groups created character types who would have to appear in order for the play to seem authentic; for another, religious images were very useful for drawing characters and creating allegory.

One interesting example of the deep questions and interesting dynamics that were practically in the air for the plucking was the conflict between those who favored light and those who favored dark. The "Golden Bride," for example, could be seen as desirable because pure or otherwise because phony, thus creating a fabulous literary device that depended on perspective — say the distinction between Roman Catholics and Calvinists.

At any rate, there persisted, at the time, to be a sizable class of wealthy Catholics from whom Shakespeare could have derived patronage.

Next up was Dr. Glenn Arbery, of Assumption College, talking about "The Problem of Catholic Piety in the Henry VI Plays":

As you'll note from his accent, Dr. Arbery is a Southern man, and it's therefore not entirely surprising that he drew parallels between Shakespeare and William Faulkner, both of whom wrote at times of social adjustment, with all of the anxieties and changing orders that such times bring. When a society is thus shaking at its core, authors come to realize more deeply what its characteristics are — who its people are — and observe what it is being urged to become. There are good and bad in both, of course, just as there are positives and negatives in both the dark and the light (as Asquith put them), and part of what makes contemporary literature so rich is authors' inclination to highlight aspects of each, explicitly or inherently as a means of encouraging their societies to preserve or discard certain aspects.

Reading between the lines of Arbery's speech, one can discern inchoate buds of a distinction being made between what makes a good man and what makes a good leader (in the context of religion and monarchy). Secular democracy, though still a good distance off, was on its way — an excellent development, to be sure. But Shakespeare's history plays warn of the sorts of men and women who will strive to be the alternative to the "good man" who is not such a good king.

After Arbery's talk (and lunch) buses took us down the length of Aquidneck Island to Stanford White's Newport Casino Theater, which has not been entirely completed, yet, but which hosted the next presentation for the conference, scenes from Hamlet performed by

Theater of the Word Incorporated interspersed with analytical narration by Joseph Pearce:

The method of presentation was an excellent and entertaining method of explaining a thesis (although it was dark and so entertaining that I didn't take notes). And the theater itself was sufficiently compelling as to make me wish I had time to write plays again.

Back on the campus of the Portsmouth Abbey School, Saturday finished with a dinner talk by Father Peter Milward, whom I understand to have led the charge of research into the Catholic dimension of Shakespeare's plays.

Fr. Milward made among the most interesting points of the weekend when he noted that persecution of Catholics had gradually increased over the 1500s, climaxing during Shakespeare's time. Ever since, the Protestants have written the history, as it were, making Shakespeare seem to be a secular writer. Now, as Milward puts it, England "is not so much anti-Catholic as anti-Christian."

So it goes. See it as evolution or progressive devolution, a society that teases its profundity away from the underlying conclusion that made it profound in the first place will drift until its philosophy is hollow and its language unable to support the many layers of true depth.

June 14, 2011

Portsmouth Institute, "The Catholic Shakespeare?," Friday, June 10

As always, the Portsmouth Institute's annual conference was an edifying and relaxing taste of high intellectual pursuit, and one can only wish such events were more regularly available... and more broadly pursued by the general public.

Rt. Rev. Dom Aidan Bellenger, the Abbot of Downside, set the scene with the opening lecture on Friday afternoon. He described the religious upheaval during Shakespeare's time, during which "targeted attacks on tradition [cut] the culture adrift from its ancient moorings." Thus Shakespeare worked in an atmosphere of "creative tension of religious uncertainties."

Following Fr. Bellenger, Dr. John Cox, an English professor at Hope College, surveyed the use of prayer in Shakespeare. Specifically, Cox addressed the question of whether the prayers in Shakespeare's plays are notably Catholic, coming to the conclusion that they certainly show him to be knowledgeable of Christian practice and not unsympathetic, but that there was nothing strikingly Catholic about them. Overall, Shakespeare appears to have taken prayer seriously, and presented it as a sort of functional activity within a comprehensible moral framework, but he's dealing with characters (many unseemly), not with exegesis.

Later in the conference, I had occasion to mention to Dr. Cox my observation that prayer is very much like play writing in that the author is composing words to be spoken to convey some idea to an audience. He offered St. Augustine's Confessions as essentially a very long prayer, and I noted somebody's comments during Cox's Q&A session citing a character's use of the word "indulgence" when petitioning the audience for applause, as if the audience were a collection of saints available for appeal.

His reply was that some critics conclude that Shakespeare began to empty the language of profundity by using such words in light theatrical context and thus diminishing their utility for describing religious concepts. I wondered if that's led to a modern period in which the language provides the author no inherent profundity at all. But it also occurs to me that the double meaning of words is a very Catholic idea — not to say that Catholics invented the device, but that (as with Transubstantiation) the religious significance of words exists as a real, almost tangible thing however used.

After Dr. Cox's talk, however, deep thoughts were swept away for the time being with a specially collected orchestra's fantastic performances of Sir William Walton's Henry V Suite and Tchaikovsky's Romeo and Juliet Fantasy Overture, under the conducting of Troy Quinn:

Then, after a typically excellent Portsmouth Abbey meal, three students from the school offered the nightcap of some scenes from Romeo and Juliet:

June 10, 2011

UPDATED: Portsmouth Institute, 2011