Childhood poverty is (almost) all about marriage.

Yet, those who care about the issue seem like they shy away from acknowledging the link. It should be central to every analysis and policy suggestion.

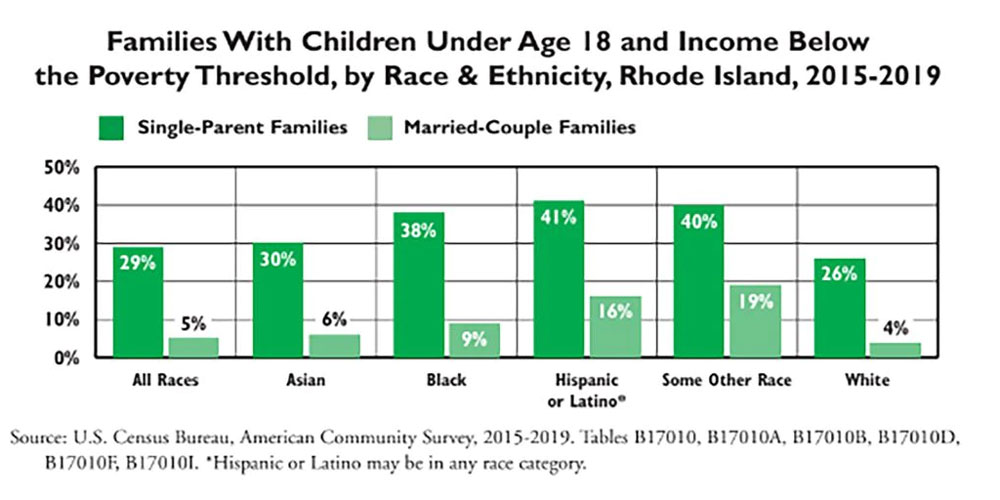

Consider the chart in this post’s featured image, which the Boston Globe’s Dan McGowan culled from the latest Rhode Island Kids Count Factbook. The title of the chart says it’s about poverty, race, and ethnicity, yet the most profound factor is the gap between single-parent families and married-couple families.

Overall the gap between Black children in poverty (27%) and White children in poverty (13%) is fourteen percentage points, a little more than double. But the gap between Black children from single-parent families and Black children from married-couple families is twenty-nine percentage points, a little more than quadruple!

According to data from the Annie Casey Foundation Kids Count Data Center, 76% of White Rhode Island children live in two-parent families. The percentage for Black Rhode Island children nearly cuts that in half, at 39%. If you want to reduce child poverty in the Ocean State, you have to talk about that. You have to advocate for policies that strengthen marriage. This is as clear as any policy analysis can be, and yet, progressive advocates downplay it.

The factbook also downplays another fact: half of all children in poverty in Rhode Island are White.* Yes, you could say that they are therefore “underrepresented,” but if we are interested in actual, living children, rather than racial categories, that is by far the most common face of child poverty in our state.

Why do advocates put forward such a distorted view of the problem and its solutions? Two reasons suggest themselves. First, talk about marriage starts to get into cultural matters and backs up against the priorities of the LGBT priorities of progressives.

Second, and perhaps more centrally, if the problem of child poverty is about race, then it’s about bigotry and it’s somebody else’s fault. If it’s about marriage, then we’re putting the onus on the people who are most responsible for their children’s well-being: the parents.

The pictures in the factbook illustrate more clearly than words what the Rhode Island Kids Count Organization wants the story to be. Of the 13 figures shown, only one is a White child, a girl — in a state where 71% of children under 18 are of that race and approximately half of them are boys. Moreover, only one child is shown with a parent, and in that case, only one parent is shown.

If helping children is truly your top priority, you don’t deliberately erase a third of them, and you don’t minimize the importance of the single-most-important factor for their well-being.

* The question of White children in poverty gets more complicated in a way that shows either the unhelpful confusion that racialist thinking begets or the insidiousness of the effort to obscure the facts.

Table 5 on page 17 of the report tallies all children by race and municipality, breaking out Hispanic or Latino from White. A summary table on page 19 shows overall child poverty to be 17% and 13% for Whites and 33% for Hispanics. Combining the numbers from these tables suggests that a little less than half of all Rhode Island children in poverty are White. In fact, a pie chart on page 37 puts the proportion at 53%.

Yet, text on page 18 insists that 72% of Rhode Island children in poverty are “Children of Color” — a term the report capitalizes but never defines. How could 72% of children in poverty be Children of Color when 53% of children in poverty are White? Obviously, some Children of Color must be White. Indeed, a note on the pie chart emphasizes that the Census asks about Hispanic ethnicity separately from race.

Digging through the five-year iteration of the Census’s table B17020 from 2019 and its race-based subtables shows that the Kids Count report uses the “White Alone” racial category for the 13% poverty number but uses the separate “White Alone (Not Hispanic or Latino)” category for the 72% claim. Oddly, the Census provides no “Black Alone (Not Hispanic or Latino)” information. And keep in mind that this still means that the biggest racial group of children in poverty are non-Hispanic Whites.

One can infer the identity-politics thinking behind these decisions. Advocates want to be able to cast poverty as a racial phenomenon in large degree, as well as to focus on a handful of urban locations in the state. In this effort, they insist that White people are privileged by virtue of the color of their skin — hence the “Children of Color” term and the non-representation of White children in the illustrations.

But in order to achieve these goals, they have to insist that an Hispanic or Latino surname makes children “Of Color,” even when they are not, in fact, of color.

[…] be changing, but people who identify as “white alone” are still 84% of the state and 71% of those under 18. Yet, in the eyes of the state Department of Education, that large majority is in the […]