Rhode Islanders shouldn’t get used to state-of-emergency government all the time.

Yesterday, June 10, in the two-thousand and twenty-first year of our Lord, Rhode Island Governor Daniel McKee, the first of his name, did sign and decree the “One Hundred and Sixty-Eighth Supplemental Emergency Declaration,” extending the state’s COVID-19 state of emergency for another month.

As is typical, the declaration contains “whereas” clauses to offer information about the declaration and its rationale. One might expect one of them to provide some description of the actual state of emergency, or at least to say something like, “whereas COVID-19 continues to present a danger to the health and well-being of the people of Rhode Island.” One would be wrong. The only rationale is that an executive order was issued on March 9, 2020. An emergency was declared, and the declaration is renewed. Deal with it.

The reason for this conspicuous omission is probably no more significant than that the executive orders are essentially formalities to get around the thirty-day time limit that state law imposes on emergencies. It is essentially a limitless state, at this point, until the governor lifts it, so a statement that it continues to be required is superfluous.

Still, it’s easy to imagine a bit of a psychological aversion in the governor’s office to articulating what the emergency actually is, nowadays, because there simply is no emergency. The state’s chief executive just isn’t willing to give up enhanced power and leave Rhode Islanders to their own devices (and their own freedom).

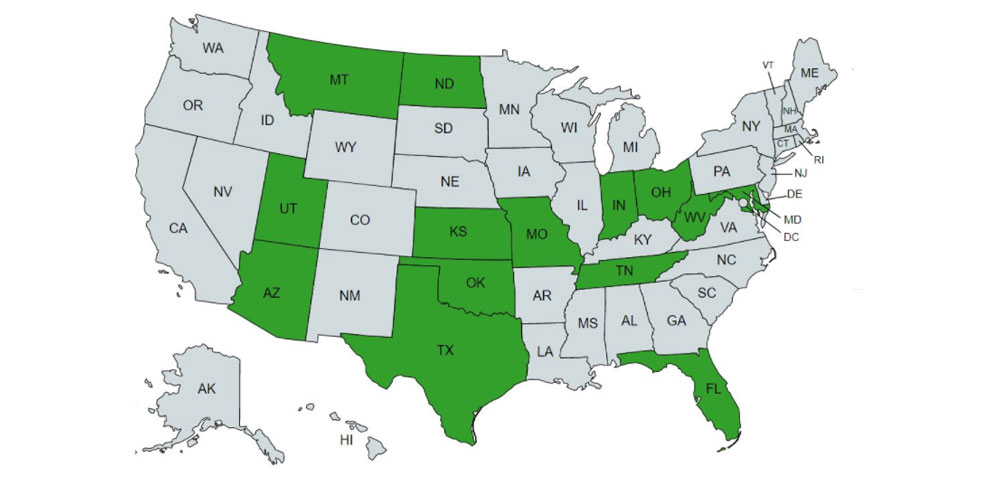

Meanwhile, Rhode Island is notably not one of the fifteen states that have taken action to limit emergency powers and public health authorities’ reach when they are declared, as Jon Miltimore reports for the Foundation for Economic Education:

If 2020 taught us anything, it’s the danger of unchecked executive power. Using emergency powers, governors and public health bureaucrats across the country took unilateral, sweeping, and indefinite measures that massively damaged livelihoods and infringed on the rights of millions of Americans. People were fined and arrested for simply gathering privately or exercising outside, walking a pet, paddling a boat on the water (alone), or taking a child to the park—even though most transmissions took place in homes and the coronavirus is rarely transmitted outdoors.

Until last March, state-level declarations of emergency were generally understood as, one, a provision for an immediate and dangerous event to which ordinary government processes could not respond quickly enough or, two, a mere formality with no real effect other than to allow the state to accept federal funding. In places like Rhode Island, such declarations can now be seen to be something very different. They have become ongoing waivers of duly passed laws concerning government transparency, election security, economic freedom, and more.

If Rhode Island’s current state of emergency is ever permitted to expire, we can be sure that officials will find them much easier to impose, in all their recently enhanced power, in the future. As a free people, we’re much too complacent about that probability.