The Left Discovers the “Time Tax,” Wants More Government

Here’s the process I discovered for actually claiming unemployment insurance in Rhode Island this year, especially if somebody successfully scammed the system in your name recently:

- Fill out the online form.

- Wait a week.

- Play that old radio-call-in-contest game by redialing the Department of Labor and Training’s number until you manage to get into the system after 10 to 15 minutes.

- Sit on hold for two to three hours.

- Talk to somebody who can help you.

- Wait for somebody to call you on an appointed day to ask you more questions.

- Miss the call because it came early in the morning and the phone didn’t actually ring.

- Call back and leave a message for the person who called you, whose message warns you only to leave a single message.

- Wait a week.

- Repeat steps 3-5 to make sure everything’s still on track.

- Answer every call as quickly as you can for the next week because you don’t know when the more-question person will get to you.

- Have a surreal, condescending conversation based on confusion over a glossary of terms you thought were interchangeable.

- Repeat steps 3-5 because there are three different sets of instructions for what counts as looking for work and a random audit some time over the next year could leave you having to pay back benefits if you pick the wrong set.

The massive government-amplified unemployment of the past year has surely amplified experiences like this and helps to explain the traction that Annie Lowrey’s article in The Atlantic about “The Time Tax” has been getting recently.

In my decade-plus of social-policy reporting, I have mostly understood these stories as facts of life. Government programs exist. People have to navigate those programs. That is how it goes. But at some point, I started thinking about these kinds of administrative burdens as the “time tax”—a levy of paperwork, aggravation, and mental effort imposed on citizens in exchange for benefits that putatively exist to help them. This time tax is a public-policy cancer, mediating every American’s relationship with the government and wasting countless precious hours of people’s time.

The issue is not that modern life comes with paperwork hassles. The issue is that American benefit programs are, as a whole, difficult and sometimes impossible for everyday citizens to use. Our public policy is crafted from red tape, entangling millions of people who are struggling to find a job, failing to feed their kids, sliding into poverty, or managing a disabling health condition.

I’ve noticed something about folks tweeting out this article in the Rhode Island Twitterverse: They seem to have little concern or awareness that the concept of a “time tax” has long been discussed among those who are not trying to get something from government, but from whom government is taking things or demanding action. That means people who are trying to build, to be productive, and to run businesses and other organizations. Lowrey paints a picture of the harried social-program applicant who’s juggling a million concerns and shouldn’t have to become an expert bureaucracy navigator, but she gives no hint that she understands the same applies on the other end of the government transaction.

It is as if she assumes those kinds of people (the manager types) are simply competent and well situated to handle the impositions of government. Despite several complaints about the scarcity of government data, particularly related to demographics, she asserts:

The time tax is worse for individuals who are struggling than for the rich; larger for Black families than for white families; harder on the sick than on the healthy. It is a regressive filter undercutting every progressive policy we have.

Remove the ideological screen from those sentences, and you’ll understand that the people Lowrey labels as “the rich” are often people struggling to achieve something else, something that will help everybody, something that has nothing to do with managing the bureaucracy.

Sure, maybe they can afford to turn the “time tax” into an “accountant, lawyer, and lobbyist tax,” but those are resources that won’t go toward the core missions that they’re pursuing. Moreover, it’s also regressive within that strata of society. The small innovator is less able to afford new taxes of any kind than is the big established player. Indeed, the only entity who can take red tape in stride is the near-monopolist who is happy to pay the additional cost because it creates a barrier to entry for possible competitors.

The time tax is real, and it should be a consideration in everything government does. The obstacle to this revelation for progressives, however, is that this spirit of unity makes it more difficult to see more government as the solution. Whether the end goal is providing a government service or imposing a government restriction, somebody has to manage the time. Either taxpayers must fund more government or the affected people must spend their own time.

To the extent that the “time tax” problem is worse in the United States, as Lowrey alleges, it’s because we still have some degree of freedom. Trying to retrofit a welfare state onto a free society produces complexities, just as trying to retrofit socialism on a free market does.

Lowrey has a fantasy that the welfare state can be made more efficient, but that means explicitly making it more expensive. The time tax, like all taxes, is a disincentive. The smaller it is, the more it’s worth applying for benefits even at the margins. And the more benefits cost, the more actual tax somebody else has to pay. Worse, the more automatic the benefits, the more beneficiaries will turn their energy toward increasing them.

The solution is not to lean into the welfare-state, but to lean toward the free market. The fundamental problems with government services are that they have no competition and that there is no separate institution on the side of the citizen. If I had (say) private unemployment insurance, I could first select the company based on price and reviews of its service (which means it has incentive not to put customers through hell). Then, if my insurer engages in abusive practices, the government is a separate institution to which I can turn as an ally.

When it’s all government… it’s all government. We’re at its mercy.

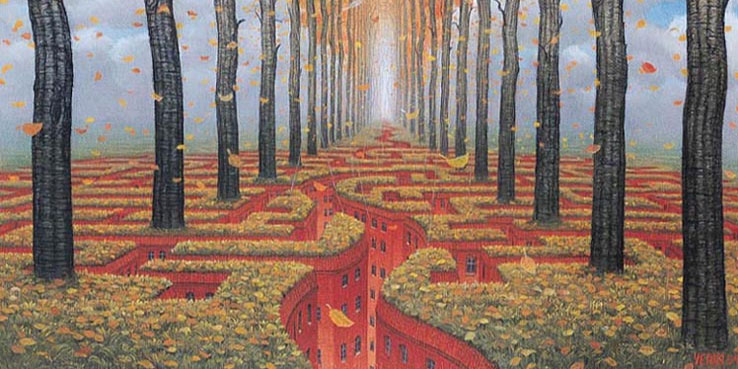

Featured image by Jacek Yerka on WikiArt.