Student loans are another crisis for the benefit of government.

Whatever one’s political leanings, the incentives of government must be understood as simply reality. Government agencies don’t have to create a product or service that people will voluntarily purchase. Rather, they must find activities for which they can justify forcing people who are not the direct beneficiaries to pay. This model is justified, in some circumstances, but its being justified does not change its nature.

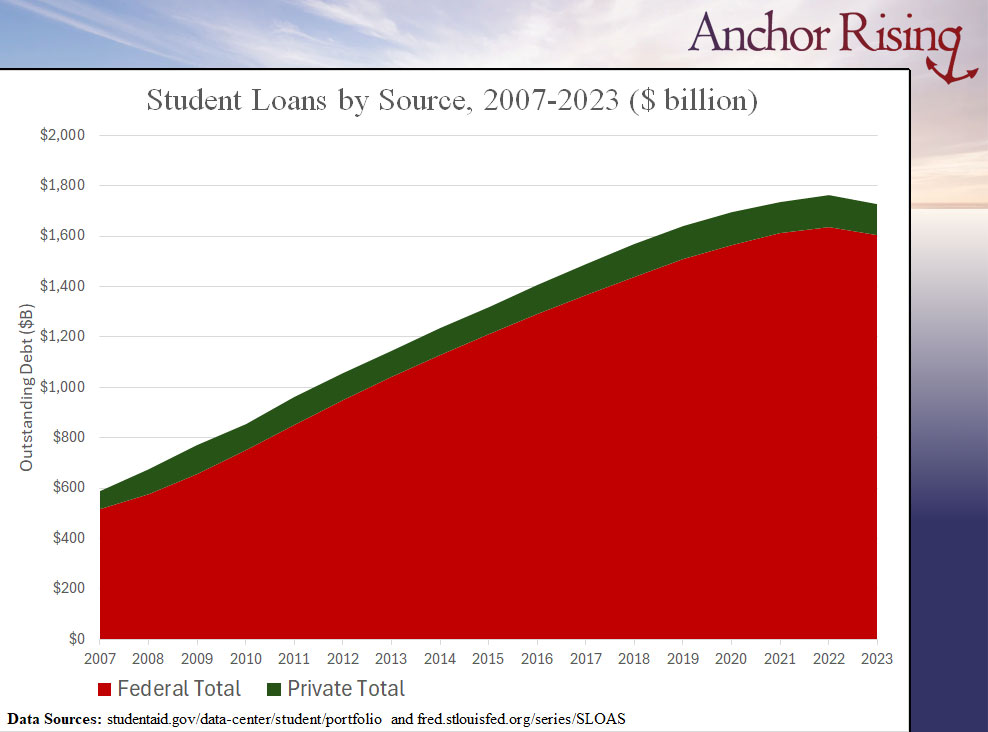

The other day, I set out to find data on student loans because talk of the Biden administration’s passing graduates’ debt on to other people seemed to have been overstated. I thought most debt came from private loans, not government-backed loans, but I was wrong. Comparing the federal student loan portfolio with total securitized student loans suggests that private loans account for just 7% of the total.

Of course, the ratio is likely to vary significantly by income level. More research would be necessary to confirm this point and put some details to it, but lower-income families are probably more likely to have high federal debt, while upper-middle-income families have more private debt and wealthy families simply pay their college bills. Keep that differential in mind while considering the following chart.

Over this period, the amount of student debt has nearly tripled, up 193%. However, federal debt has grown 211%, while private debt has grown “only” 70%. During this time, the number of Americans ages 15 to 24 increased by only 1.4%, while the number enrolled in college has increased by just 5.5%. In short, we can infer that easy access to federal debt has encouraged some additional enrollment, but it has contributed to inflation of tuition by an order of magnitude more. And while it would certainly require a separate inquiry, the general sense one gets is that, if anything, the quality of education has gone down.

Now look at the other side of the ledger. That down-tick in debt over the past year is attributable to the Biden Administration’s transfer from the accounts of the students and graduates to the account of the American taxpayer. More importantly, the amount is hardly significant in the face of the increase, which is the observation that leads to the key point.

Commentators rightly complain that responsible borrowers and those who never went to college are being made to pay for other people’s degrees, and to note that many of those degrees are likely to be useless, reflecting something more like a four-year vacation from life than a communally beneficial training of future workers and leaders. In my view, however, the more-significant effect is on the borrowers themselves. They have been made serfs and products of the federal government.

The model of what I’ve called the “government plantation” is one in which politicians and other government officials cultivate recipients of government services (in this case, financial lending) for which they can charge other people. The cultivators take a cut of the money from the payers while also reaping the reward of votes from those who have been made dependent.

We see this process in operation with student debt. Government policy has transformed the debt load for higher education from reasonable to crushing, and one party, the Democrats, dangles the promise of relief in exchange for votes (even if it must be done without legal authority). But the relief it provides is only a fraction of the burden it has imposed, leaving its ability to promise more relief entirely intact.

With this arrangement, as with many others, the end result is not a benefit to the recipient or the payer, but a loss of freedom for all. Little wonder the powerful spend so much time cultivating, above all, a sense of animosity and division.

Featured image by Justin Katz using Dall-E 3 and Photoshop AI.