The United States: That Kid Who Had to Learn About Debt the Hard Way

I’ll admit that my path to financial education involved direct experience denying the reality that new credit is not a financial windfall.

The summer after my freshman year at college, all of my friends had been working since graduation, instead of taking classes, and were planning the annual trip down to the beach-and-boardwalk town of Wildwood, New Jersey. I had absolutely no way of paying to join them… until that first credit card arrived in the mail. Suddenly, the week’s adventure became affordable. Or rather, suddenly I had a way to get people to give me the goods and services I wanted at the time I wanted them, even though I could not afford them.

Inasmuch as I had already begun working and would continue to do so instead of returning to college, I reasoned I could pay it off easily. Only… it wasn’t just the week in Wildwood. I mean, my new housemate and I needed a television, didn’t we? And how could I work without a car? And doesn’t a young man deserve to live it up a little on the weekends?

Thus does the debt trap turn economic life on its head. The story of working and saving, hitting milestones that joyfully herald new tiers of security and possibility flips and becomes the addict’s story of desperately looking for ways to avoid hitting a wall. Each time an infusion of cash or credit comes in from somewhere, it feels like easy sailing for a time. That feeling builds on itself because no infusion can be big enough to fill the hole, so it is taken as an opportunity to take a break from worrying.

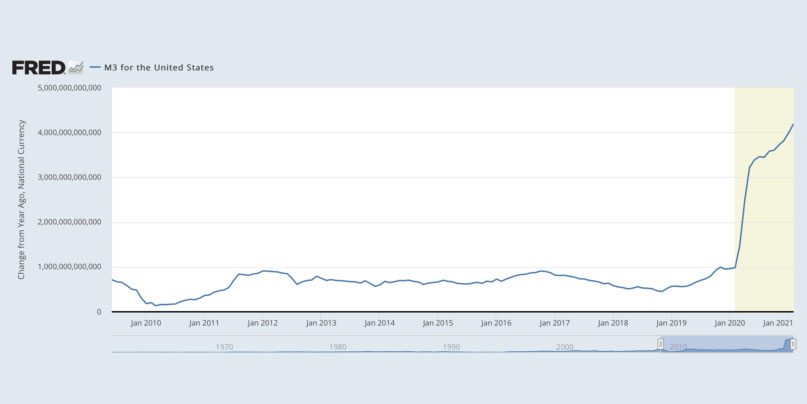

The impression is growing that this is our country’s current predicament, and Jeffrey Tucker has pulled together some charts to give it shape for the American Institute for Economic Research:

An owner of the bar explained to me that he has been closed for a full year and yet miraculously still survives, thanks to vast infusions of government money to cover his rent and upkeep and sustain essential employees. He is looking forward to reopening but is having a hard time finding employees. Many have moved to Florida. Others, he said, “are happy to live off government money rather than work.”

His main puzzle is how it can be true that the government has the resources to sustain so many businesses in a full year of lockdowns. The money is falling like manna from heaven.

“From all my years in business, every instinct tells me that this can’t be right. It might work for a little while but someone has to pay these bills. There is no magic money tree out there to achieve such things.”

The bar owner’s experience has taught him how the world works, and no matter what the fancy economic theories might say about monetary policy, this all just feels off. Thus the strange shapes shown an Tucker’s charts, which are sourced from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis’s Frequently Requested Economic Data (FRED) tool:

- As shown in the featured image for this post, the money supply increased at more than four times the rate that had been the recent norm.

- The country’s gross domestic product (GDP) has surpassed its pre-COVID level, despite large portions of the economy that have not yet recovered (and may never).

- Consumer spending is up about 30%, despite so many people still not working.

- Spending on housing is past the point at which the real estate bubble popped a little more than a decade ago.

On the flip side:

- Inflation appears to be starting on an upward swing.

- Government spending has been increasing at more than eight times the rate that was the case before COVID.

- Even with GDP recovered, the government’s debt as a percentage thereof is through the roof.

This can’t be right.

At least a young adult’s credit card bills come in the mail once a month, bringing the reminder of both a ceiling to the debt and the eventual need to pay it off. The problem with this amount of cash in the economy and this level of debt and the uncharted territory that “Modern Monetary Theory” puts us in is that we don’t really know when the bill will arrive or even how much we will be allowed to borrow. Moreover, so much of the allure is that we, the people, won’t have to work as hard to get these riches, which means we can’t really be sure we’ll have income to cover it.