They don’t even know that they are Christians.

In the middle of the Sixteenth Century, St. Francis Xavier wrote to his friend, St. Ignatius of Loyola, of his experience ministering to Christians in India:

We have visited the villages of the new converts who accepted the Christian religion a few years ago. No Portuguese live here, the country is so utterly barren and poor. The native Christians have no priests. They know only that they are Christians. There is nobody to say Mass for them; nobody to teach them the Creed, the Our Father, the Hail Mary and the Commandments of God’s Law.

Children would not leave him alone with requests to teach them prayers. “If only someone could educate them in the Christian way of life, I have no doubt that they would make excellent Christians.” The letter closes with a lamentation that the intellectuals of Europe were not undertaking the mission of educating such as these, rather than digging ever more deeply into their books.

Times have changed.

For some years, I’ve been on the lookout for a sort of Post Testament. The Old Testament tells the history of Israel’s relationship with God, and the New Testament describes the coming of the Messiah and the activities of his first apostles. In our time, “new” is entirely relative; the book is two millennia old!

Where is the new New Testament, which I’d call the Post Testament out of deference to the Gospels? What is God’s story since the apostles were busy writing letters to new Christians about the faith? The available texts are far too numerous to canonize — official letters, catechisms, poetry, proclamations, stories, histories of saints, histories of nations, and on and on. The lack of some book summarizing the story contributes to the impression that the story of the God of Israel is done. How might we understand what He has been up to all these centuries?

The closest thing I’ve found is a relatively recent history by the non-Christian writer Tom Holland, Dominion. As he briefly summarizes on a recent episode of the Andrew Klavan podcast, his conclusion is that Christianity has essentially become the default belief system of the planet — the water in which modern society swims. Even the often-anti-Christian “woke” activists can be understood as a sect of the faith, except that, in contrast with Francis Xavier’s Indian students, they know not that they are Christians.

Moreover, rattling the cages of the Ivory Towers these days, as Francis Xavier fantasized about doing four-and-a-half centuries ago, would only shake loose more evangelists for the modern heresy.

Four-and-a-half centuries Before Christ, Malachi wrote the last book of the Old Testament, as compiled by the Roman Catholic Church. The short scripture has blistering words about the condition of Israel:

A son honors his father, and a servant fears his master;

If then I am a father, where is the honor due to me?

So says the Lord of hosts to you, O priests, who despise his name.

But you ask, “How have we despised your name?”

By offering polluted food on my altar!…

You[, the people,] have wearied the Lord with your words,

yet you say, “How have we wearied him?”

By your saying, “Every evildoer is good in the sight of the Lord,

And he is pleased with him”; or else, “Where is the just God?”

The pages of God’s calendar turn slowly, to human eyes, but they turn. From Malachi comes the promise, “Lo, I am sending my messenger to prepare the way before me.” Today, the second Sunday of Advent, as we approach Christmas and celebration of the Messiah’s birth, Catholic churches read from the Gospel According to Luke, in which John the Baptist calls the Jews of Jordan to “prepare the way of the Lord.”

The prophesied messenger comes and tells us to prepare. St. Francis Xavier from his mission calls on us to teach. As our subconsciously Christian civilization wearies the Lord with words of perverted justice to the point that many think His story has concluded, we should wonder why we wait to be called.

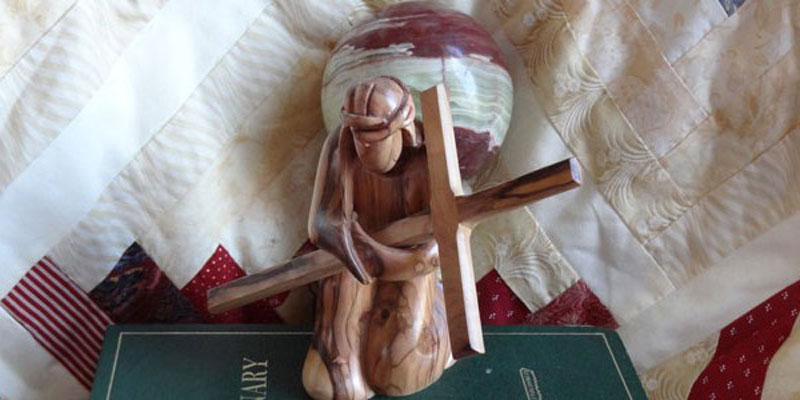

Featured image by Justin Katz.