What does a double-timing Providence principal tell us about that job in Rhode Island?

News about former Providence principal Michael Redmond, and the fact that for a period of time he was working full time (during the same hours) for both the school district of Providence and the Washington, D.C., school district (remotely), has been broadly reported in Rhode Island. Unfortunately, the public debate falls quickly into the lines that divide Rhode Island insiders, above the heads (as it were) of regular parents and residents.

Redmond was a hire of former superintendent Harrison Peters, who was hired by Education Commissioner Angélica Infante-Green after a report by Johns Hopkins University researchers horrified the nation. Consequently, the divide between the commissioner and the teachers’ unions defines every such controversy.

I’d recommend stepping back, however, and attempting to read Alexa Gagosz’s Boston Globe coverage independently of that inside-politics framing:

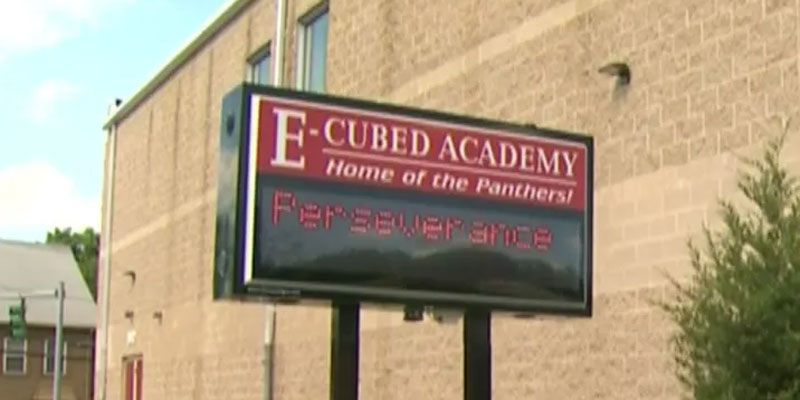

Michael Redmond, who was hired as E-Cubed Academy’s new principal in July 2020, admitted to continuing to work virtually as the assistant principal at the Stephen E. Kramer Middle School in Washington, D.C., for 17 weeks after he started working full-time for Providence Public Schools.

According to a violation notice issued by the District of Columbia’s Board of Ethics and Government Accountability earlier this month, Redmond admitted to working on weekdays from 8:30 a.m. until 3:15 p.m. at Providence Public Schools while also working weekdays from 8:45 a.m. to 3:15 p.m. for D.C. Public Schools.

Rhode Islanders might note, sardonically, that it was D.C. that caught Redmond, not RI, but that could just be the luck of D.C.’s having had a whistleblower who cared. The observation shining forth from the story is that he managed this for more than four months, and it took somebody “alerting” the D.C. district for it to come to light.

At least according to Redmond, speaking to the Washington Post, he had “highly effective ratings” in D.C. and was “receiving excellent marks” in Providence. From his perspective, he was able to perform to expectations at both jobs.

There is the key question that the insiders don’t want to ask. Is this true? Was he meeting expectations? If so, his achievement doesn’t excuse his actions, but it does lead to another very important question: How pathetically low are expectations for school principals in Rhode Island (and D.C., for that matter) that somebody could work two jobs at the same time and still meet them?

That question gets to the core of Rhode Island’s public education problem — indeed, the problem with our public sector across the board. Thanks to labor unions, the system is set up as a jobs program for adults, not an organization to accomplish critical community tasks and meet the needs of children and others. Consequently, the system focuses more on what it can reasonably request of workers than what it can reasonably expect on behalf of the people being served.

Professionals in the private sector tend to see their jobs as their responsibility, and however many hours it takes to do the work, that’s what they do, often without being able to bill somebody for their time. Not so in the public sector, where powerful political players work to reduce accountability and ensure that every second is compensated at taxpayer expense.

If you want to know how a case like Redmond’s can happen, the answer lies there, not in the spat between the state, the district, and the union about who is ultimately calling the shots.