Urban parents should take note of the suburbs.

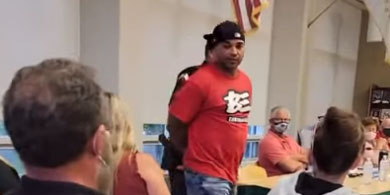

A major theme currently peppering my news feed from across the country is suburban parents being arrested while speaking out at school committee meetings. John DePetro has video of one such man, Jeremy Palmer, at a school committee meeting in the Chariho district. Another parent in that district, Kelly Sullivan, describes the multiracial opposition to trends in that school district on Ocean State Current.

For this post, let’s not get caught up in argument about what these parents are up in arms about. The point is that they’re attending meetings and speaking out against something they perceive as harmful to their children, even as it results in their being taken out of public meetings in handcuffs.

Now turn to Providence, from Steph Machado on WPRI:

Data reviewed by Target 12 shows student absenteeism skyrocketed in Providence during the pandemic, with every single public school in the district reporting an increase in chronic absenteeism, defined as a student missing 10% or more of school days. (That’s 18 days or more in a full school year.)

As of the end of April, 60% of Providence students had been chronically absent this school year, according to the data, which includes both virtual and in-person learners. During the same time period last school year, 37% of students were chronically absent — a number that state leaders had already targeted for improvement when they took control of the district shortly before the pandemic.

High schools saw the highest rates of chronic absence. Mount Pleasant High School topped the list, with 84% of its students chronically absent from September through April, according to the most recently available data. That’s up from 47% during the same time frame last year.

Machado allows activists to bury the data in a hose-spray of excuses. Standard journalistic writing calls for reporters to put the key news first and then widen the loop with details from there. In this case, before getting to the headline data, Machado allows Youth in Action activist Olubunmi Olatunji several paragraphs to promote anecdotes about students’ challenges concentrating in packed apartments and having to work.

Those points are all relevant, but search the article for the word “union” — as in “teachers union” — and you won’t find it. Mention of the ongoing contract disputes, with the union fighting changes after a devastating report about school quality in the city two years ago? Nothing. Local and national efforts of teachers unions to keep school lockdowns going as long as possible? Silence.

We do hear from Deputy Superintendent of Learning Khechara Bradford that “attendance didn’t seem as compulsory as it did before,” because the district “wanted everyone to take their health and safety first.”

By all means, let’s talk about the hardship that Gina Raimondo’s shutdown of Rhode Island caused for the people of Rhode Island, but that’s not the whole story. Far from working harder to mitigate the harm to the children under their care, the school district and its teachers union deepened the hole they were falling in.

Where are the parents being arrested at government meetings for speaking out?