Weird how every insight other than the testimony of vested interests in the system turns out to be suspicious to the vested interests.

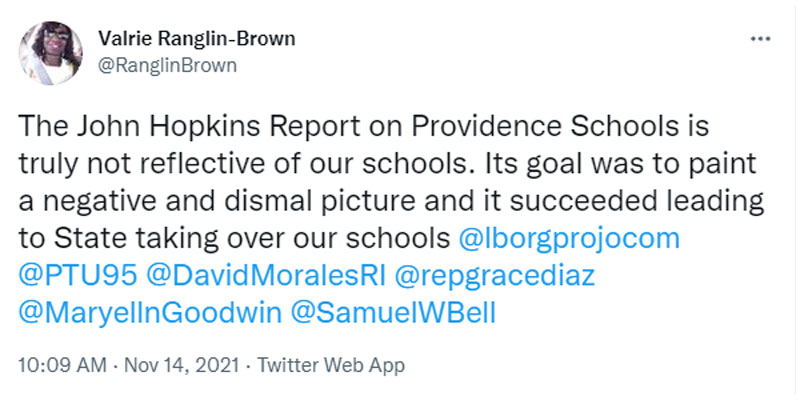

Putting aside the insinuation of bad faith on the part of people with whom she disagrees, Providence English teacher Valrie Ranglin-Brown — sister of Rhode Island Representative Marcia Ranglin-Vassell (D, Providence) — makes a point well worth considering:

The John Hopkins Report on Providence Schools is truly not reflective of our schools. Its goal was to paint a negative and dismal picture and it succeeded leading to State taking over our schools …

Who cares that our students are also working to put food on the family’s table and keep a roof over their heads. I care when my Ss works night loses a patient (s) in the nursing home. “GM Miss , I have more bad news another of my patient died.” Who can tell me we are failing?

In a recent episode of his podcast, Revisionist History, Malcolm Gladwell raises just this point when exploring the U.S. News and World Report ranking of historically Black college or university (HBCU) Dillard University. Dillard doesn’t rank very highly, even though its outcomes for the population it seeks to serve are arguably better than that population’s outcomes at the most elite institutions. The university fails only in that it hasn’t cultivated a reputation for eliteness, but it succeeds by tailoring education to its actual students, in a way very much in line with Ranglin-Brown’s priorities for handling her own students.

That said, the Johns Hopkins report and, similarly, standardized test scores are not U.S. News and World Report rankings. The report was an in-person analysis of a specific school system, and the scores are straightforward assessments of what we expect students to learn in school.

Maybe they’re both missing something important or emphasizing something not so important, but that’s a case that has to be made descriptively. Simply taking the word of people professionally vested in the status quo that there’s something nobody else understands would be a travesty of deliberate ignorance. If every attempt at an objective measure screams for dramatic reform, voices against reform have to come up with more than complaints and conspiracy theories.

Stepping back a bit, though, Ranglin-Brown’s testimony actually supports the call for major change. Her point is that Providence schools are not failing, but rather, that they are forced to grapple with unique challenges. Fair enough, and true. But that means the solution is to redirect public resources away from schools that can’t address the problem and toward services and programs that can.

This won’t be done in Rhode Island, however, because the most powerful special interests in the state will not accept any solution that is calls for “different” rather than “more.” We shouldn’t question the concern expressed by people who devote their lives to educating disadvantaged children, but we can’t ignore their own interests, which lie in protecting a system that cannot succeed.