Conflicts like this can be nothing more than bureaucratic squabbles. They can also be evidence of a move toward a Communist China–esque absorption of religious organizations. And they can also be mere bureaucratic squabbles that prepare the ground for government absorption of religious organizations.

[Open full post]The Archdiocese for the Military Services (AMS) slammed Walter Reed National Military Medical Center for issuing a “cease and desist order” to Holy Name College, a community of Franciscan Catholic priests and brothers who have provided pastoral care to troops and veterans at Walter Reed for nearly two decades, just before Holy Week.

On WNRI 1380 AM/95.1 FM, John DePetro and Justin Katz discuss:

- A state worker’s mysterious offense.

- Connors moves a notch around the insider wheel.

- How McKee is digging an economic hole.

- Who’s out and who’s in? An update on the CD1 race.

- Who made PVD’s ATV problem so difficult?

Featured image from Shutterstock.

[Open full post]To what extent, do you think, is our current predicament caused by a feedback loop of blindness? Perhaps the people investigating society’s questions are actually incapable of considering some possibilities for ideological reasons. They therefore craft policies and advance cultural changes whose outcomes they cannot measure because of the blind spot with which they began.

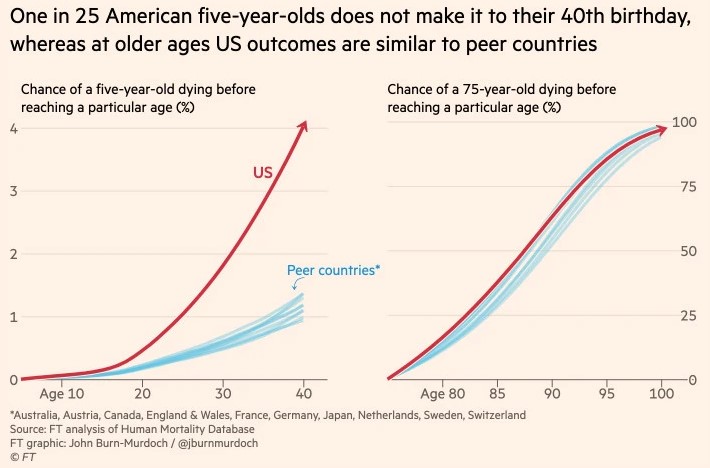

A few days ago, John Burn-Murdoch sent ripples throughout social media with a Financial Times article titled, “Why are Americans dying so young?” (Putting the title in a search engine may provide you a link you can read without subscribing.) Burn-Murdoch doesn’t investigate the answer or even tally deaths by various causes. Rather, in the clickbait method of our day, he produces charts like the following:

The primary point to remember when viewing such charts is to check the axes. Yes, Burn-Murdoch shows American children to be four times more likely to have died by the age of 40, but that’s still only 4% of them. His other charts do similar things, such as cutting the vertical axis to make a couple years of longer life, on average, look like a 50% increase.

Such methods aren’t necessarily tricks; sometimes we do want to zoom in to spot differences. Magnitude is important to remember, however, when we’re seeking causes. The United States is incredibly diverse in just about every way it’s possible to be diverse — geography, demographics, wealth, etc. Comparing us to England or to a selected collection of “peer countries” might not be as appropriate as comparing us with a similarly sized area somewhere else on the planet. A few years of life or a few percentage points of difference are easy to make up by changing the dataset.

Such gaps are easy to make up in other ways, too. One factor that Burns-Murdoch does not consider, for example, is abortion. Data from Johnston’s Archive for the United States and the United Kingdom suggests that one in eight (12.4%) children conceived in the United States is aborted, compared with 1 in 4 (24.8%) in the United Kingdom. Start Burn-Murdoch’s clock at conception rather than the age of 5, and the picture is very different.

This isn’t only a point about the proper starting point of human life. A society’s comfort with killing children before they exit the womb will tend to eliminate those who might have faced challenges. Out of every 100 children conceived, the United States gives an extra 13 a chance at life. If only three of those would have been aborted in the United Kingdom because they tested positive for genetic problems or because their mothers were destitute and unlikely to raise them healthily, then the gap in the left chart above disappears.

Whether it is better for those children to live or to die before they’re self-aware is a cultural question for which we’ll have different answers. That said, investigators like Burn-Murdoch probably won’t even identify it as a relevant question as they’re compiling statistics to fault the United States for its health care system, gun laws, or some other cause of the day.

Featured image by Rene Bernal on Unsplash.

[Open full post]On WNRI 1380 AM/95.1 FM, John DePetro and Justin Katz discuss:

- RI becomes a Wall Street Journal poster child for Democrats’ need for bailouts and big budgets

- Arlene Violet’s plea to stay in public eye

- McKee’s search for people to blame

- Rhode Island government- the newest real estate developer

- Who’s out and who’s in? An update on the CD1 race.

- McKee and Silva: the disastrous duo

Featured image from Shutterstock.

[Open full post]Talk about housing has been all the rage in Rhode Island over the past year. Unfortunately (and tellingly), it doesn’t seem to be a policy area in which activists, politicians, and journalists believe data ought to be front and center. Sure, we get numbers about the effects of the problem — housing costs $X; Y number of people are homeless; it takes a middle-income family Z number of months of income to cover their housing — but nobody seems inclined to use data to understand why those conditions hold.

Folks do seem pretty confident, however, that a big part of the problem is local zoning and a reluctance to accept multi-family housing in every corner of the state. Progressive activist and politician Cynthia Mendes made an April Fools joke about Rhode Island “remov[ing] the zoning ban on multi-family homes” to “swiftly eliminate the classist practice of single family only exclusionary zoning!”

While not as extreme, Democrat Speaker of the House Joseph Shekarchi recently unveiled a package of bills with the following explanation:

“We are experiencing a housing crisis in Rhode Island, and it is a homelessness crisis as well – our state simply does not have enough housing, and the folks at the low end of the socio-economic spectrum are feeling the brunt of it,” Democrat Shekarchi said at a State House news conference to unveil the legislation.

While such legislation tends to require a degree of parsing I haven’t done, two of the provisions would give all homeowners the right to add “accessory apartments,” whether under the roof or separate from the main house, by right, without zoning permission. This seems like a de facto ban on truly single-family housing zoning. In any event, the implication is clearly that the state needs more density and apartments. The legislature is fighting, in the words of Providence Journal reporter Patrick Anderson, “the dark arts used by housing-averse municipalities.”

But here’s an interesting fact I haven’t seen anybody note in the Ocean State: According to data from the U.S. Census, Rhode Island has the third-smallest percentage of housing that is single family, after New York and Massachusetts. Only 60% of Rhode Islanders report living in such homes — making ours one of only nine states for which that number is lower than 70%. Rhode Island, New York, and Massachusetts are all known for high housing prices, which goes pretty far toward ruling out single-family housing as the key culprit. In fact, matching the U.S. News ranking of “The 10 States With the Most Affordable Housing” produces no observable correlation with their single-family ranks.

Iowa is #1 in affordability, but #20 in single-family home percentage. West Virginia is #8 in affordability and has the highest percentage of single-family homes. Affordable state #2 is Ohio, which is 29th for single-family homes. (None of the ten most-affordable states rank lower than Ohio for single-family homes.)

One might do better to look at the percentage of land owned by government, although it is clearly not sufficiently explanatory. Among the top 10 states for affordability, the percentage of land that isn’t privately owned averages less than 10%. Massachusetts, New York, and Rhode Island average over 15%.

To the extent there’s correlation here, however, I’d suggest its probably related to some other factor. States that are doing whatever it is that produces unaffordable housing also tend to take more land off the housing market for government purposes and suppress single-family homes, for that matter. What that something is, I don’t specifically know, but Rhode Islanders should remember that there are two ways to make things affordable: lower the price of those things or ensure enough opportunity that people can earn the money to afford them. Rhode Island should focus on the latter.

Featured image by Kostiantyn Li on Unsplash.

[Open full post]Guest: Jessica Drew-Day, Jessica@jessicaDrewDay.com

Host: Darlene D’Arezzo

Description: Jessica Drew-Day shares with us how she learned to begin to exercise her political citizenship. The process she engaged in helped her learn more about how Rhode Island state government works and her journey empowered her to become a candidate for the RI House of Representatives. She shares the process she went through and the things she learned in a step by step manner. Her message is simple and assuring: try it; you can do it too!

On WNRI 1380 AM/95.1 FM, John DePetro and Justin Katz discuss:

- Rhode Island FC’s search for a new stadium, as Pawtucket Stadium is yet to be built

- Borrowing (instead of raising) money for the Superman building

- Quattrocchi and Kislak’s pedophilia debacle

- What Powers has to watch as the new RIGOP chairman

- How RI government represents the underpass homeless

- Who’s out and who’s in? An update on the CD1 race.

Featured image from Shutterstock.

[Open full post]It’s interesting to watch these partisan ideologues bash the newspaper that contributed so much to their careers. One wonders whether they’ve ever considered whether their work-product and the journalistic culture they’ve perpetuated has contributed to the paper’s plight:

Now that it is no-longer-proposed, we are free to look at Fane Tower renderings in detail, beyond the gut reaction that it is odd and would be misplaced in Providence. Structurally, the building would have been akin to a tree trunk that began to split near the ground. The strength comes from the middle, providing the support for the flaring ends. Rhode Islanders should contemplate the visual metaphor.

Years ago, I came to the conclusion that the problem with U.S. politics and governance is not that it’s too conservative or too progressive, but that our system was no longer extracting the best from each impulse. A contingent that insists that we keep moving is valuable, and a contingent that insists on slowing down so as to preserve what is important is also valuable. As we become more divided, culturally, we’re losing the central support to make these tendencies better together than separate.

Rhode Island’s peculiar trait appears to be marrying this division within the same movements and individuals. We have progressives who don’t want anything to change — at least anything that’s important to their day-to-day lives. They’ll champion the continuing cultural revolution in which they can partake only as a matter of fashion, but when it comes down to it, they want the capital’s skyline to remain locked in time. They want jobs for workers and housing for low-income families, but they don’t want anything that is distinctly a business change their view as they drive home.

On the level of special interests, the situation is arguably worse. We’ve got the NIMBYs, to be sure, who insist that things should change but “not in my back yard,” but we’ve also got the radical progressives whose demand is that all changes serve their narrow ideology. On the other hand, the state has no business interests to speak of to offset these groups, all of them having been absorbed by the fundamentally corrupt government-insider gang whose interest is not business or development per se, but only that they be able to take a cut of whatever does happen to happen.

In a culturally homogenous society, the culture could provide the ballast to keep these factions from tipping the boat. In a diverse state, the political system could play a similar role by making it in politicians’ interest to triangulate. When the self-serving interests of those politicians represent the only “conservative” impulse, however — that is, the only restraint on radical change is that they must be able to profit from it — the system falls apart.

With the Fane Tower project killed off, the Pawtucket soccer stadium on the ropes, and the Superman Building project groaning under its own weight, we may be seeing the tipping collapse of the edifice that allowed insiders to pretend things were fine as the federal government kept money flowing after the real estate bubble popped and then COVID saved the state government’s fiscal neck. As the illusion crumbles, Rhode Islanders need to find our center, and we can only hope its foundation is still intact.

[Open full post]