On WNRI 1380 AM/95.1 FM, John DePetro and Justin Katz discuss:

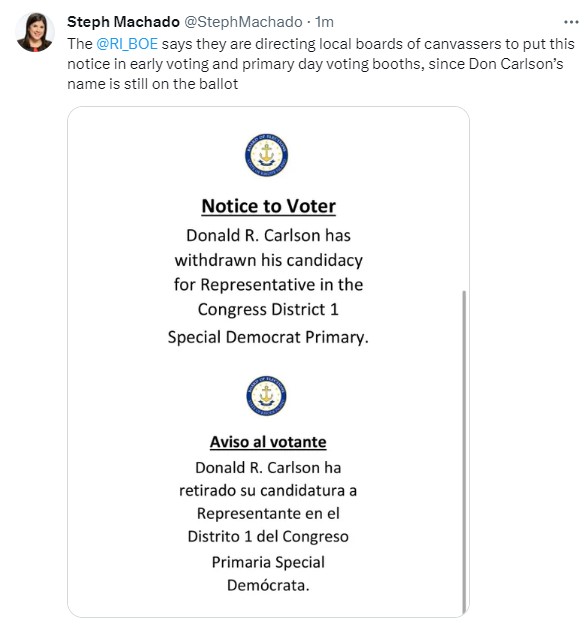

- Don Carlson and allies’ complete mismanagement of the scandal

- Sabina Matos’s complete incompetence as a politician

- The Republican candidates’ complete lack of strategy

- What Regunberg gets that his competition does not

Featured image from Shutterstock.

[Open full post]This is precisely the sort of application of supposed common sense without due process that incrementally undermines our rights.

There is no process for a candidate to remove him or herself from the ballot, and as far as I know, there are no standards in law or regulation for the Board of Elections to determine when it can post signage in a polling place discouraging voters from choosing a candidate. This is very, very dangerous.

Voters can choose to vote for Carlson regardless of his statements, and if they don’t know he’s insisted he’s withdrawn, then maybe they deserve to see their votes thrown away.

Take particular note that Carlson used the word “suspend,” not “withdraw,” in his announcement (which has no legal effect). The BOE should not be doing this.

[Open full post]Rhode Island Current, a newcomer to the Ocean State’s media landscape, recently published an article by Nancy Lavin asking the perennial question, “What’s with RI jobs data?” Over the decades of my interest in the topic, this ambiguity has been a running theme. The state has no (and cannot have any) economic confidence.

We’re like a sick person in the constant throes of self-evaluation looking for any sign that maybe… maybe… there’s hope he or she is on the upswing. I feel a little less congested today. My temperature is down a tenth of a degree. There’s not quite as much edge to my cough this morning.

In this case, the specific mystery that captured Lavin’s interest is how the state can be losing jobs even as more Rhode Islanders report that they’re employed. She asks a handful of the standard experts, and they provide a handful of the standard answers: Most prominently, the employment numbers, which come from surveys asking if a person has worked at all recently, include those who work in other states (including remote work), whereas the jobs numbers, which come from the government reports of businesses located in the state, do not.

Department of Labor and Training information and operations manager Donna Murray comes close to a point that’s less often made when she mentions the “gig economy.” The jobs number doesn’t include independent contractors, so to the extent businesses are using their services, rather than hiring employees, people will be employed without “jobs,” technically speaking.

This isn’t really new, though. Independent contractors are essentially bosses of their own businesses, and they’re indistinguishable from one-person shops. Your self-employed plumber, for instance, will be employed but not count as a job. For decades, Rhode Island has done conspicuously well (from a certain perspective) when it comes to business starts, and analysis has led me to conclude that the reason is people can’t find suitable jobs.

They look for work and can’t find it (or they lose it). Then they start doing anything they can for money (gig economy). If their businesses begin to grow, Rhode Island regulations tend to put them out of business once they start to become more official “small businesses.” So, then they lose hope and leave for a healthier state.

In other words, Lavin’s article may miss a key point. In RI, the gig economy isn’t only another option. Our terrible tax and regulatory policy discourages job creation, forcing them to piece together an income.

Increasingly, all that remains are government-centric service jobs (as evidenced by the industries Lavin notes are growing). As government becomes the primary industry of the state, policy shifts to support the need to import “clients” for its services and to find money from somebody else (either taxing the productive or snagging gifts from the feds). This — what I’ve called the “company state” or “government plantation” — in turn makes jobs more difficult, reinforcing the detrimental cycle.

Featured image by Shaojie on Unsplash.

[Open full post]Lieutenant Governor Sabina Matos’s attempt to tar competitor Gabe Amos for — get this — having ties to Home Depot is fascinating:

He wants voters to focus on his work as a public servant and to ignore the fact that he was a registered lobbyist for Home Depot despite the company’s ties to the far-right agenda, earning tens of thousands of dollars for his work.

- Amo says “we must all be steadfast in our advocacy for the LGBTQ+ community” but was a paid lobbyist for Home Depot after the company donated $1,825,500 to 111 anti-LGBTQ politicians from 2017-2018.

- He says he will fight back against MAGA Republicans, but he lobbied for Home Depot in 2019, despite calls to boycott the company during that time because of its co-founder full throated support of Donald Trump’s re-election

- Home Depot’s co-founder Bernie Marcus donated $7 million to Trump’s campaign in 2016.

- An analysis found that Home Depot was the single biggest corporate donor to 2020 election objectors, contributing over $265,000 to lawmakers dubbed the “Sedition Caucus”

- Home Depot has contributed tens of thousands to legislators who are anti-choice, anti-LGBTQ, anti-voting rights, and insurrectionists.

The core deceit, here, is to extend the degrees of separation through which a political stain can carry, with a close second being the use of labels in lieu of facts. The first bullet above does both: Readers must rely on Matos’s unsubstantiated claim and then stain Amo for associating with a company (one degree of separation) that has had some sort of dealings with various politicians around the country (two degrees of separation).

Both are lessons of recognizable manipulation strategies that progressives use repeatedly. For instance, politicians vote on a wide variety of legislation applying myriad rationales. Activists then go through and pick and choose sets of litmus tests to which they apply an indiscriminate label like “anti-LGBTQ politician.” Usually the translation is “people who veer in the slightest bit from our most extreme position,” although they reserve the right to excuse any given politician for reason of political expediency.

In this case, though, note the target. Matos (our lieutenant governor, remember) implicitly assumes Rhode Islanders will readily think of Home Depot as a bastion of evil bigotry. This company is a familiar part of most of our lives. It employes hundreds, or maybe thousands, of Rhode Islanders and is a massive part of our economy across multiple industries and people’s quality of life.

None of that matters to a radical like Matos. With opportunity for the slightest bit of political advantage, she’ll tear it all down.

In short, she’s a consummate example of the cynical and destructive power of progressivism. Rhode Islanders should remove her at first opportunity and rethink any positive view of progressives they may have.

Featured image by Moritz Mentges on Unsplash.

[Open full post]On WNRI 1380 AM/95.1 FM, John DePetro and Justin Katz discuss:

- All the ways in which Matos is seeming desperate

- Raimondo puts the U.S. next in line

- An RIGOP “debate” in the absence of strategy

- Bartholomew others a Block Island bar

Featured image from Sabina Matos’s campaign website.

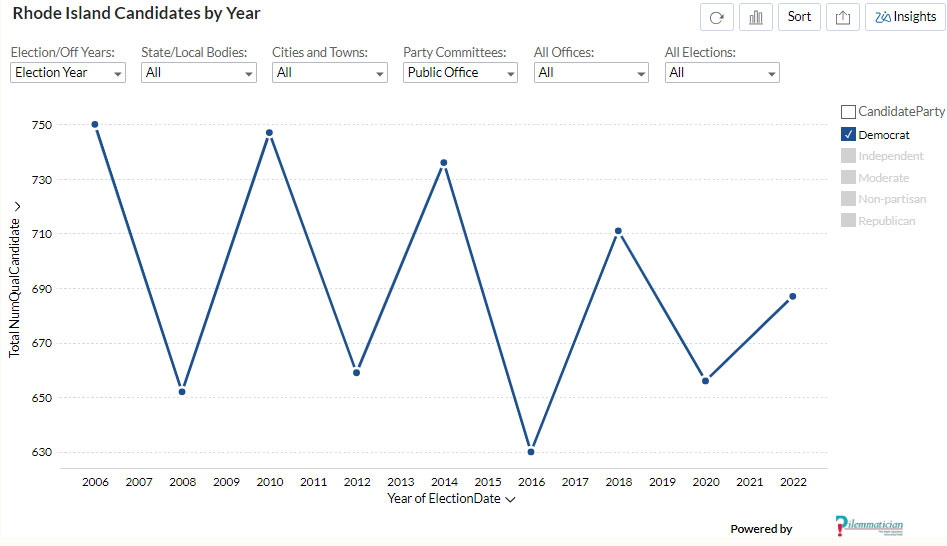

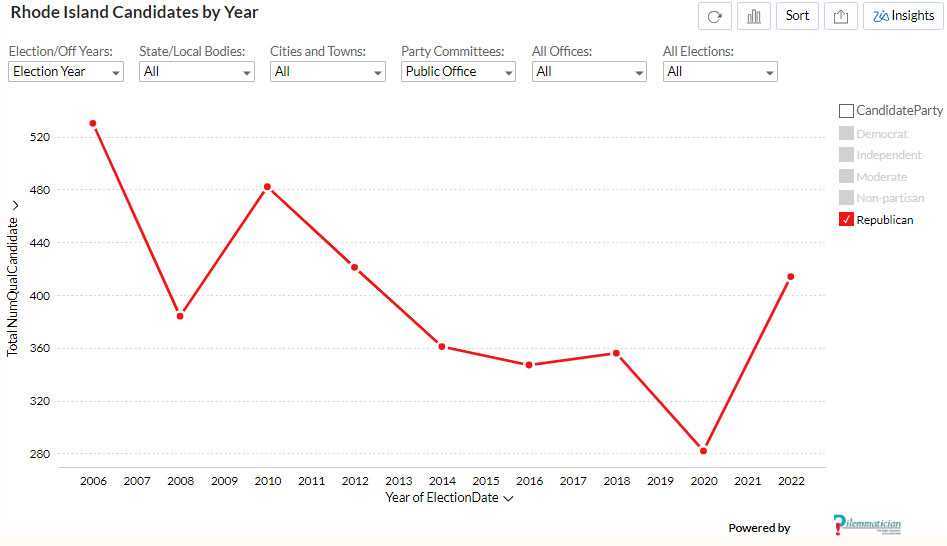

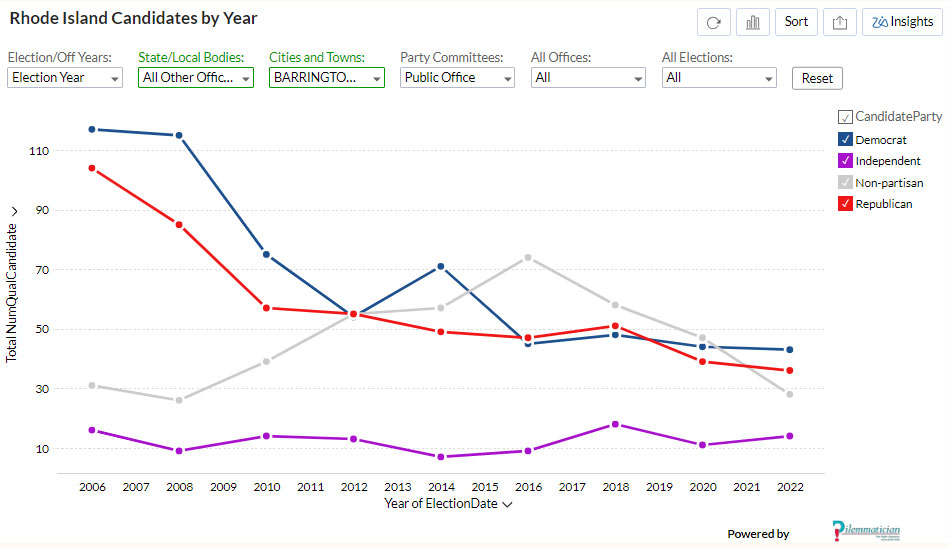

[Open full post]In part to answer curiosity about whether regulation of our elections in Rhode Island (through campaign finance laws) has been reducing participation, Anchor Rising has added an interactive tool to our People’s Data Armory. The page provides a filterable chart (with access to the underlying data) that shows the number of candidates who have qualified for the ballot during Rhode Island elections.

A decrease in candidates is what one would suspect. In business, regulation as a disincentive — a sort of tax — that increases the cost of startup and operation, which reduces incentive to participate at the margins. (That means people who find it a close, “marginal,” decision between starting a business or doing something else will be more likely to do the other thing. Of course, the same calculation applies if the something else is opening the same business somewhere else.)

State and local politics has the additional quality that many such roles are still considered to be an exercise of civic responsibility, so the pay isn’t great and is often nominal or nonexistent. This consideration is suggestive of another area worthy of investigation beyond the scope of this dataset: A candidate can have incentive to take a low-or-no-paying job if he or she can make money by some other means while or after holding that job. Thus, regulation of campaigns has the effect not only of limiting choice, but also of making it more likely the remaining choices will lean toward corruption.

Although such trends in political participation have many contributing causes, Rhode Island’s elections have, indeed, seen a pronounced decline in candidate participation, particularly among Republicans. Taking note of the fact that the line for Democrats tends swing substantially between gubernatorial and presidential years (with the former being higher), Democrats have seen an 8% drop in qualified candidates for public office at all levels.

Republicans’ decrease has been several times more dramatic. Even with a surge in 2022, 22% fewer Republicans qualified for office in 2022 than 2006. The decrease had been 47% in 2020.

Readers can play with the various filters to get as specific to offices or races as they like. In that direction, I’d note that “legislative” offices (General Assembly, municipal councils, and school committees) maintained their candidate bases reasonably well, at least among Democrats; Republicans were on the decline until the 2022 surge. Given that these are typically among the archetypal low-to-no-pay (but powerful) government jobs, I’d repeat my warning above that we could be selecting for people who have some other way to make money from their positions.

The following chart, in contrast, shows the very dramatic drop in the number of qualified candidates for all other local offices. Here, we’re looking at local administrators (mayors, clerks, treasurers, and so on) as well as other boards that are frequently seen as pure civic responsibility roles (budget committees, planning commissions, etc.). Whatever the significance of the offices themselves, they are crucial as stepping-stones for people who are not career politicians or do not benefit through special interest ties (like labor unions), but just get the bug to participate in government.

Again, many factors contribute to these trends. Anybody participating in hyperlocal governance knows that modern life’s many distractions have reduced engagement. Still, the decrease is unhealthy — limiting voters’ choices, tilting incentives toward corruption, and separating We the People from the exercise of government authority. Whatever other factors may be in play, the steadily increasing regulation of political engagement certainly hasn’t helped and should be reformed.

As a starting point, legislators should begin discussing an exemption for some of the hyperlocal offices that are essentially volunteer opportunities for civic-minded Rhode Islanders. This would limit regulation to those with greater responsibility and, probably, a little more experience. Then, if we see recovery in the last chart of this post, we could make a strong case that electoral regulation is limiting our choices and our rights as citizens and balance that reality against the stated benefits of campaign finance.

Featured image by Josh Carter on Unsplash.

[Open full post]On WNRI 1380 AM/95.1 FM, John DePetro and Justin Katz discuss:

- Money from nowhere for the stadium

- The latest variation on cross-over voting

- A need for strategy in the Leonard campaign

- McGowan’s Regunberg boost

- Ahlquist illustrates progressives falsity on a Woonsocket park bench

- Morgan’s double race

Featured image from Shutterstock.

[Open full post]Toward the end of a generally compelling episode of EconTalk, psychiatrist Marcus Ramos slips in a term that may shed a light on some of the discord and lunacy we’re seeing in our society these days: liberation psychiatry, which he explains thus:

There are other ways of looking at mental illness from the past and through history in other settings outside of the United States–like in Latin America as well as Africa in post-colonial context–where mental health has specifically been linked to political and social mobilization, and in certain contexts they would consider it liberation. …

… it starts with a very simple idea, which is that: You cannot be mentally–you can’t have mental health unless you’re liberated from the social structures that are making you sick. And, if that’s the case, then there needs to be this palliative work, as you put it, that you’re talking where you support the person who’s being made ill by these larger social structures. But, there also needs to be political work on the part of the practitioner with their patients, to resist–to liberate them from–the things that are making them sick in society.

… The last, sort of–the way this loop completes, I think in many ways, is that: not only was the political action in many ways effective unevenly so, but in many ways effective in getting certain services for this community that had been affected. But also, psychologically, the process of politically organizing to speak back to the thing that had hurt you was psychologically therapeutic.

It’s unsurprising that the push to turn psychiatry into a form of political activism is originating in South America, which produced liberation theology and the politicized pedagogy of Paulo Freire that is ravaging America’s education system. In the realm of psychiatry, however, the problem is somewhat easier to see: If you build your activity, whether theology, education, or psychiatry, around political activism, you must necessarily find things to blame, and you must assume the solutions you come up with truly address the cause of the problems to which you’re responding. This is obviously vulnerable to both error and manipulation that serves some other political interest. The likelihood is high that neither the patient nor the therapist will have sufficient understanding to identify the real essential problem and prescribe the precise policy to resolve it, yet they must come up with something as a basic requirement of the treatment.

A related problem is that the patient won’t always win. If people feel they have identified an injustice and used political activism as a type of therapy, their condition could worsen if they lose the political fight, which they may very well do, and which they may very well deserve to do if they’ve chosen their cause poorly. Naturally, if they’ve been pointed at a cause for ulterior reasons, this worsening of their condition is a benefit, not a problem, because the cure will be to dive more deeply into the cause.

This approach could easily devolve into nothing but a scapegoating mechanism that generates a stream of impressionable activist troops. Whether one ascribes this inevitable sequence to an ideological conspiracy, the workings of Satan, or simply the random-but-constrained operation of human nature, the incentives line up for a deadly cocktail, undermining our society in a desperate search for the root causes of discomfort. Conspicuously, that destruction reduces stability, and thereby increases both the likelihood of tragedies and the psychological instability of the people.

As EconTalk host Russ Roberts points out, our society has already gone a long way toward undermining sources of belonging and meaning (family, religion, etc.). Now, the deconstructionist forces are attacking even the security of our trust in a stable reality. They’ve done this through fearmongering (“climate change”), identity politics (“trans”), and encouragement to reckless, destabilizing behavior (“pleasure-based sex education”).

The self-reinforcing cycle certainly seems designed, rather than accidental: The movement initiates psychological instability and then prescribes political activism as a combined therapy and solution. All that remains is to choose a political target that serves the special interest guiding the process. To the extent their stated intentions are genuine, academics like Ramos and others rolling the stone toward the hill seem not to be cognizant of the risk. Ramos laments the influence of powerful moneyed interests in psychiatry and elsewhere but doesn’t appear to see that powerful moneyed interests are ideally positioned to manipulate the process he’d set in motion.

The rest of us must challenge this movement at each step and reinforce in our policies and our own lives the necessary solutions — family, religion, limited government, civil rights, and community. As we do so, we’ll have to withstand the attacks on the institutions in which to bond, because the activists will fling epithets and tar them as evil (e.g., “white supremacy”), and they’ll see assaulting us verbally and physically as part of their therapy. But our burden can be made lighter with reminders that, yes, we are sane, and what our attackers need most is the stability we’re seeking to establish.

Featured image from Shutterstock.

[Open full post]Whether Rhode Island’s health insurers are overreaching in their requested premium increases for the upcoming year is a question I lack the time and expertise to answer, but I can say that a recent news splash from Rhode Island Attorney General Peter Neronha has enough markers of political propaganda to justify suspicion about his findings. Worse, the local news media do nothing but amplify his spin, leaving Rhode Islanders severely underinformed and therefore unable to make reasoned decisions.

Let’s trace the inquiry backwards from a key section of Alexa Gagosz’s Boston Globe article:

Many of these companies have posted enormous profits in recent years, Neronha said. Cigna, for example, requested an increase of 5.9 percent in the large group market, after it reported a total adjusted revenue of more than $180 billion in 2022 and its profit topped $1.2 billion. The company also projected adjusted revenue of $187 billion this year.

Aetna, which is owned by Woonsocket-based CVS Health, requested a 6.6 percent rate increase in the large group market after posting a $91.4 billion revenue in 2022. Aetna ultimately contributed to CVS’s $4.1 billion profit in 2022. On Tuesday, Neronha stressed in a statement that the insurers’ increased financial resources should be “passed on to benefit consumers” by making their coverage more affordable.

The first thing to note is that Gagosz simply repackaged key parts of Neronha’s press release. “Enormous profits,” for instance, is his language, not hers, and she presented his talking points without doing any work to provide context. Although she has updated her article since I brought this problem up on Tuesday on Twitter, she originally didn’t address the fact that revenue is not profits, the latter of which must take into account the level of expenditures. A business can have massive revenue and still experience a loss, which the attorney general — the attorney general! — glossed over in his press release.

That’s only the start of the obvious spin. Following the links in Neronha’s press release to his actual reports brings up more questions. Notably, most of his contentious claims about revenue don’t come from analysis, but from casual online research, which is sometimes analysis of analysis of actual data. By the time we get to the press release and the news articles about it, important context is completely lost.

For the lead example of “enormous profits,” Neronha cites Cigna, but according to his own report, that company covers a single group of 325 people in Rhode Island. The company’s profits — which, according to Gagosz, amount to less than 1% of its revenue — have hardly anything at all to do with the Ocean State.

The other examples have similar problems. Note the carefully crafted language in Gagosz’s article: “Aetna ultimately contributed to CVS’s $4.1 billion profit in 2022.” She cites the profit of the entire retail, pharmacy, clinic, and insurance conglomerate that is CVS as if that is a reflection of its insurance arm! She also skips the information in the first paragraph of her source, which acknowledges that CVS’s profits were down nearly by half from the prior year.

In that context, it’s significant to note that Rhode Island’s insurance commissioner limited insurers to a 1% profit last year. In other words, Neronha’s implicit case is that these companies should redistribute their profits from other states and entirely separate types of business activity to Rhode Islanders in the form of artificially low rates. That’s all well and good as long as the state can force it, but businesses don’t have to offer insurance in our state at all, and the less competition we have, the more political influence the remainders will have.

The most important bit of information we lose in these propagandistic headlines, however, is that Rhode Island’s high insurance rates are more a function of bad policy from the State House, not corporate greed. Mandates limit choice, which drives up price. Squeeze the insurers, and they’ll squeeze the providers, and we’ll get fewer providers… which will drive up the price of those who remain until the market finds an equilibrium. We can be sure, in all this, that Rhode Islanders will lose out on the deal, because as the willingness to spin us shows, nobody’s really trying to keep us well informed or supported.

Featured image from Shutterstock.

[Open full post]On WNRI 1380 AM/95.1 FM, John DePetro and Justin Katz discuss:

- Campaign finance and election cheating

- Regunberg brings in the big guns (his parents)

- CD1 competitors play the race card

- RIGOP’s lack of message

Featured image by Kostiantyn Li on Unsplash.

[Open full post]