A reddit post by somebody claiming to be a student at a “specialized high school” in New York City has been getting a fair bit of attention. (Note that the post has been edited, with some commentary found in earlier screen captures deleted.) The student describes a school day during the Omicron surge as something like a Stephen King novel (back when Stephen King was good):

… 90% of the bathrooms were full of students swabbing their noses and taking their tests. I had one kid ask me — with his mask down, by the way — whether a “faint line was positive,” proceeding to show me his positive COVID test. I told him to go the nurse. One student tested positive IN THE AUDITORIUM, and a few students started screaming and ran away from him. There was now a lack of available seats given there was a COVID-positive student within the middle of the auditorium. …

One teacher flat out left his class 5 mins into the lesson and didn’t return because he was developing symptoms and didn’t believe it safe to spread to his class.

Conspicuously, the anecdote about the teacher (which is not in the latest version of the post) is the only mention at all of symptoms, and in that instance, it could have been anything. Was it a tickle in the teacher’s throat? A mild feeling of impending congestion? Who knows? The point is that all of the drama and fear is related to testing positive.

One needn’t dismiss the danger of COVID to find it strange that the virus itself is an afterthought in many of the horror stories about its spread. Indeed, the student’s experience could apply even to an illness that didn’t exist, as long as tests could be contrived that gave a positive at some random interval. As the parent of multiple school-aged children during this pandemic, I can testify that the fear is of the disruption and loss of opportunities that testing positive would bring.

One recalls this experiment at the University of Arizona in 2013:

Conducted in an office on the UA campus, the study included about 80 participants, some of whom received droplets on their hands at the start of a normal work day. While most of those droplets were plain water, one person unknowingly received a droplet containing artificial viruses mimicking the cold, the flu and a stomach bug.

Employees were instructed to go about their day as usual. After about four hours, researchers sampled commonly touched surfaces in the office, as well as employees’ hands, and found that more than 50 percent of surfaces and employees were infected with at least one of the viruses.

Now imagine one of those old-fashioned psychological experiments from the ’50s or ’60s in which researchers deceived participants and, in this case, told everybody the “artificial viruses” weren’t harmless. The experiment would have generated a panic not unlike what we see at the NYC school.

This isn’t to say that we should be cavalier about the coronavirus, but context and focus is important, and we’re really heavily focused on positive tests — the increasingly infamous “case” count. Don’t be surprised to learn in years to come that mass testing can produce similarly frightening evidence of “super spreader” events for viruses that we’ve lived with for centuries.

Featured image by the CDC on Unsplash.

[Open full post]I’ve long speculated that Rhode Islanders start businesses at a healthy clip because the economy isn’t producing work at the level of hours and/or pay that they want. That is why the Ocean State sees a lot of businesses struggle when they start formalizing things. All the business stuff is too complicated, especially when the folks starting the businesses just want to do what people in their professions do. Management is not really the job they were intending on building for themselves.

So, it’s not surprising to see Grant Welker of the Boston Business Journal report that Rhode Island saw some record business starts last year, when ordinary work patters were disrupted.

Welker also points to a SurePayroll study of startup-related Google searches. It turns out, the most-searched prospect in the Ocean State was for starting a fitness company. One imagines unemployed Rhode Islanders establishing fitness routines for themselves during lockdown and thinking, “Hey, I could do this for a living!”

While a concentration on good health is nice to see, I can’t help but think that, economically speaking, Massachusetts’s result as the only state in the country for which “consulting” is healthier. Of course, it’s difficult to know what consulting even means to people!

[Open full post]Law and order is shifting in the United States. On one hand, it seems as if our justice system is increasingly reluctant to hold criminals accountable, with sometimes tragic outcomes like the recent death of an East Greenwich teen in a car crash. Increasing assaults on college students in Rhode Island’s capital city raise no concerns in official halls (including the news media). Drugs are being decriminalized. Our border is wide open.

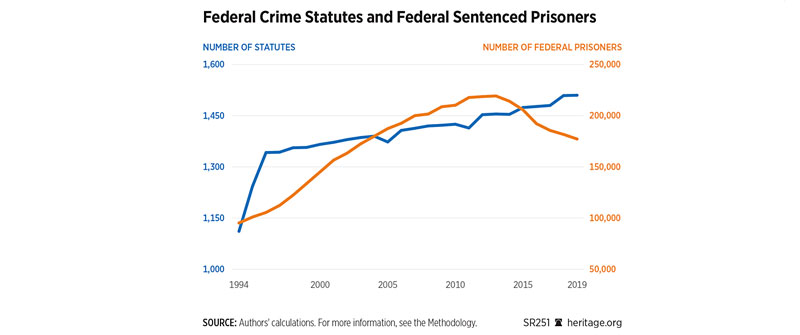

And yet, Heritage researchers, led by GianCarlo Canaparo, must resort to algorithms even to count the number of federal crimes. The obvious question is how the average American can be expected to know what activity is considered criminal when researchers can’t even count the crimes?

The Roman Emperor Caligula, infamous for his caprice and malice, published new tax laws in small font and hung them high atop pillars to entrap the people into unknowingly violating them. For more than 2,000 years, this sort of behavior has been condemned as fundamentally unjust because no person can fairly be expected to obey a law that is unknowable. A government might hide its laws by putting them out of sight, but it achieves the same result by passing so many laws that no citizen could possibly read them all. James Madison made this point in The Federalist Papers saying, “It will be of little avail to the people that the laws are made by men of their own choice if the laws be so voluminous that they cannot be read.” This problem is most dire when the laws at issue are criminal ones because violators may be deprived of liberty and, in some cases, even life. …

Some are so vague that even if they were known, no reasonable person could understand what they mean. Others forbid behavior that no person exercising ordinary good judgment would expect to be a crime. And in some cases, it is a federal crime to violate the laws of other countries. Former U.S. Attorney General Edwin Meese III, who, perhaps more than any other public figure, has brought attention to this problem, has written that this profusion of scattered, vague, and unintuitive criminal laws “create[s] traps for the innocent but unwary and threaten[s] to make criminals out of those who are doing their best to be respectable, law abiding citizens.” In other words, the United States has accomplished by carelessness what Caligula accomplished by scheme.

Combine the two trends noted thus far in this post, and you get the chart shown as its featured image. From 1994 to around 2012, the number of federal prisoners shows a steep increase. Oddly, however, that total has been falling steeply.

Three possibilities come quickly to mind. The first is that scrupulous Americans may take a little time to learn about the federal government’s laws but then change their behavior so as to return to their formerly law-abiding condition; this does not seem likely and, if true, would raise frightening thoughts about the government’s ability to dictate people’s behavior. The second possibility is that the federal government is creating crimes that nobody commits or that agencies lack the ability or will to enforce, which creates potential for arbitrary prosecution when officials find a person whom they’d like to determine is a criminal. The third is that a general sense that there are too many crimes on the books is leading to leniency when it comes to other crimes that officials opt not to prosecute, even though most people would agree that they should be crimes.

In all cases, the credibility of the system comes into question, and American life becomes more difficult — and more dangerous — to live, because the law is understood as something not to taken with either moral or practical seriousness as written.

[Open full post]Black Lives Matter-RI PAC 12/13/21 from John Carlevale on Vimeo.

Harrison Tuttle of Black Lives Matter Rhode Island PAC speaks with Richard August about his organization and possible his own possible campaign for office.

[Open full post]What a joke this all is:

The open government coalition ACCESS/RI and a number of municipal officials had urged McKee to provide the authorization for remote meetings as COVID-19 cases soar across Rhode Island. The East Providence City Council was among the entities forced to cancel a scheduled meeting this week after members tested positive for the virus.

Rhode Island’s Open Meetings Act usually requires public bodies such as city councils and school boards to meet in person and in public. But in 2020 former Gov. Gina Raimondo signed an executive order suspending parts of that law so meetings could take place online or on the phone — with public access — during the pandemic. …

Senate President Dominick Ruggerio rejected McKee’s suggestion, saying his chamber wanted to hold more hearings before making any changes to the Open Meetings Act. He instead urged McKee to issue a new executive order, saying they had discussed the issue “ad nauseam.”

John Marion, executive director of Common Cause Rhode Island, argued that a legislative fix was still the best long-term option.

“We need to work toward permanent changes to the Open Meetings Act that will allow for greater remote participation while safeguarding the public interest so that in the future we don’t have to rely on executive orders,” Marion tweeted Thursday. He also said he was pleased that the language of McKee’s order lays out “the administration’s guidance for public bodies.”

The legislature specifically refused to act on this matter. Under what conceivable authority, then, does the governor proclaim that public bodies are “relieved from the prohibitions regarding use of telephonic or electronic communication to conduct meetings contained in Rhode Island General Laws § 42-46-5(b)”? That isn’t how any of this works.

It’s not as if public officials can’t spread out on a stage and conduct meetings in locations with plenty of seating for those who wish to attend. Plenty of taxpayer dollars have been spent on large public spaces.

And these innovations come with the “pleased” blessing of a so-called good-government group!

Simply put, we do not have the rule of law in Rhode Island. The law is whatever a handful of elites say it is. Meanwhile, government agencies can return to their super-control of who can speak at their meetings. The declaration that everybody should have remote access to view meetings is joined with the reality that nobody has in person access to them.

How little we care about the way in which we’re governed in Rhode Island these days.

Featured image by Compare Fibre on Unsplash.

[Open full post]Did you know only eight Rhode Island communities have laws against the menace of snowball fighting?!?!

- Charlestown

- Glocester

- Jamestown

- Newport

- North Kingstown

- Warwick

- West Warwick

- Woonsocket

Over the recent years of the pandemic, the Rhode Island General Assembly has proven its concern for the big issues, like banning the release of balloons into the air and the automatic provision of plastic straws… not to mention imposing new burdens on companies that employ nurses. Legislators should really get on this snowball issue!

[Open full post]The Rhode Island Public Expenditures Council (RIPEC) notes that Rhode Island’s downward slide on the Tax Foundation Business Tax Climate Index continues, with the Ocean State exiting the 30-something range on the bad side for the first time since 2017, at 40. The only saving graces are that Connecticut has been stuck at 47 forever and changes in corporate taxes, property taxes, and unemployment insurance taxes dropped Massachusetts dramatically in 2020, and it hasn’t recovered.

We should look at that as opportunity, though, not (in our decision makers’ usual practice) as a reason not to worry.

This is where I start to differ from RIPEC in my analysis. Their recommendations lead with a call for addressing high property taxes in our state, but I’m not so sure that’s the right answer. Rhode Island’s problem isn’t that it’s particularly bad in any particular area (although 49th in unemployment insurance taxes is obviously a downside for business), but that we’re not very good in any of them.

We should take a clinical look at the attributes of our state and determine what tax structure would be ideal. In doing that, by the way, we must resist the urge to impose too much of our vision of what sort of economic activity we want to have.

Consider this: multiple states in the top 10 have certain rankings toward the back of the pack. New Hampshire (#6) is in the 40s for corporate taxes, property taxes, and unemployment insurance taxes. Nevada (#7) is down there in sales taxes and unemployment insurance taxes. Tennessee (#8) hits people hard on sales tax. Note the contrast. It depends where you are, what your geography is, and what your probable mix of industries and population is.

So what sort of state is Rhode Island? This is the perfect question to transform into a massive public conversation. Forget all those Rhode Island Foundation events that attempt to put everything about RI on a whiteboard and herd insiders toward left-wing conclusions. Narrow the conversation down to the half-dozen main buckets of tax revenue and take a real look at our state in that context.

It’s a beautiful place in a great location, with a lot of cultural and tourist-drawing features with a scenically diverse character packed into a small area. In short, Rhode Island is a great place to be. So, where the government looks to collect its operating revenue should focus on where the value is: being here. That’s the property tax.

But if we’re going to settle ourselves in and be taxed for being here, we need to find ways to bring money from elsewhere into our state to keep our economy going. That means we should be much lighter with the taxes on doing things, so the lightest touch should be on sales tax, followed by corporate tax, followed by income tax. Regulation plays in, too, such that we should make it cheap and easy to do things here.

For a small state in a wealthy region where every town is near a border, this sets up a virtuous flow. A focus on justifying a high cost of being here will put emphasis on key attributes like property taxes. Meanwhile, the incentive to do things here will lead people who live nearby to come here, bringing their money with them. As it therefore becomes more valuable to be here, our property and our economic activity will make presence in the state more valuable.

This conversation could go in a whole lot of directions, from regulation to education to social policy, and I may not be right on any or all of it, but it’s the sort of conversation we should be having. Frankly, I think Rhode Islanders are capable and eager to have such conversations and are being held back only by insiders’ reluctance to have real conversations that might put them in the position of defending their selfish interests.

Featured image by Justin Katz.

[Open full post]Writing for Heritage, Tim Murtaugh laments the continued credibility drain from the mainstream media:

It’s obvious that the media’s hatred for Donald Trump colored nearly everything they wrote or said during his presidency. But one hoped that after he left the White House, the media might recover a little objectivity.

Sadly, a review of 2021 shows that in many cases, it simply did not happen.

My read is that many mainstream journalists bought the lies that (1) Donald Trump was uniquely dangerous to the world and (2) systemic racism exists and infects the hearts of all white people, so they thought their self-professed objectivity had to bend a little. Over the four years of the Trump administration, however, they discovered that they really, really liked letting their biases run wild.

They won’t let those biases go until they have no choice, and it may very well require news organizations actually to replace their personnel rather than relying on the same people to put their overt prejudices back in a bottle.

[Open full post]Via Instapundit comes a telling story out of Washington University in St. Louis:

Student leaders at Washington University in St. Louis want school officials to evict the “disproportionately wealthy and white” men in campus fraternities and give their buildings to “historically marginalized” groups.

Writing in Student Life for himself and almost 50 leaders of WashU student organizations, Student Union President Ranen Miao whines that while campus fraternities have a total of nine houses on campus, while underrepresented organizations have but three.

Miao, a triple major in political science, sociology, and women, gender, and sexuality studies, contends the fraternities “have done nothing to earn the space they occupy.”

Note, by the way, that fraternities don’t discriminate by race, whereas the identity groups that want their houses do.

Radicalism always comes to this. The activists don’t value what a targeted group does or represents, so they lay a moral claim to be given what that group has. There is no endpoint. When the group his beaten and smashed to have minority standing, the progressives will simply shift to “there is no place here for them” rhetoric.

This is fascism.

[Open full post]A friend recently told me about a Massachusetts school that is explicitly leveraging peer pressure to influence families’ medical decisions related to COVID. The initiative seems to encourage a form of bullying that is unhealthy for both the students applying and the students receiving the pressure, and it reminded me of past initiatives that gave me misgivings.

Even as far back as the ’90s (and even as I was swept along in it), the push to have children guilt their parents about smoking seemed somehow inappropriate for schools. The explicit teaching of values also has had a religious feel implicitly at odds with the Establishment Clause in the First Amendment. Indeed, while it has not appeared to have originated in schools (yet), encouragement among progressives to pester family members about ideological policy generally during family gatherings has become the stuff of memes and parody.

Each step of this sort makes the next one easier. Encouraging students to move their parents toward the obviously healthy decision to quit smoking established the principle that schools could serve such purposes. Mandatory vaccination against horrible diseases transmissible in a school setting with religious exemptions became, in Rhode Island, mandatory vaccination against a sexually transmitted disease and is now becoming mandatory follow-up vaccinations for a disease that hardly affects children… and with no exemptions.

These things ratchet because a ninth-level crisis isn’t much better than the tenth-level crisis that justified a new imposition and on down the scale.

To be sure, human relations are gray and fluid, and limits often arise not from stark thresholds but simply because a critical mass of people aren’t willing to tolerate the next stage of erosion. This protection is fleeting, though, and only awaiting an excuse.

Thus, Jon Miltimore highlights, for the Foundation for Economic Education an academic’s argument that governments sometimes have to edge into authoritarianism in order to remain legitimate. Specifically, the American Political Science Review of Cambridge University published an essay by assistant professor of political theory Ross Mittiga of the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile arguing that this principle of legitimacy was proven during the COVID pandemic. Naturally, Mittiga drew this lesson in order to apply it to “climate change,” which many skeptics have long seen as an excuse for authoritarianism awaiting sufficient fear. Miltimore writes:

Say what you will about Mittiga’s proposal—which is myopic and dangerous—his logic is sound. If “legitimate” governments embrace authoritarian measures to combat a deadly pandemic that poses a genuine threat to humans, why should they not embrace authoritarian measures to combat climate change, which many argue poses an even greater threat?

There’s a popular meme among libertarians: “If you allow politicians to break the law during emergencies, they will create an emergency to break the law.”

Exactly. We can implement all the safeguards for freedom we want, but every exception will create incentive for power-seekers to find reasons that they apply. COVID turned the ratchet such that provisions to address an immediate emergency could apply to a long-term crisis. Well, anything can be sold as a long-term crisis if the rewards of money and power are high enough.

Featured image by Zulmary Saavedra on Unsplash.

[Open full post]