Stephen Skoly considers a run for CD1, Neil deMause talks publicly backed stadiums, Joseph Allen on AI, Mike Davis talks about Senator Whitehouse and the Supreme Court, and Mike Stenhouse of the RI Center for Freedom and Prosperity.

Featured image from Shutterstock.

[Open full post]Announcing the move of his cable news show to Twitter, Tucker Carlson suggests that most of what mainstream journalists report is factually true, but their stories are chosen and constructed so as to paint a completely false image of reality. Take Rhode Island education as an example.

As long as I’ve been following the story, government-run education in Rhode Island has been expensive and ineffective relative to other states (let alone to private options and the world). Just a few years ago, a team from Johns Hopkins University conducted a review of education in Providence, and the Wall Street Journal characterized its findings as “An Education Horror Show.” As a result, the state took over the schools, but without any signs of improvement. Why?

Because the teacher unions dug in, and Education Commissioner Angelica Infante-Green (then newly appointed) attempted to work with them. Whether you agree with me that her decision (urged by the politically ambitious Democrat governor, Gina Raimondo, no doubt) was a cataclysmic mistake or see it as a necessity, even if challenging, you simply must acknowledge that the unions are central to the story of Rhode Island education.

And yet, a single four-month-old story in GoLocalProv is the only instance I can find covering John Lancellotta’s lawsuit against the West Warwick school department alleging that he was let go because he exercised his constitutionally guaranteed right not to pay dues to a teacher union. Why?

Because for a variety of reasons journalists don’t want to help spread the information that teachers don’t have to join their local unions. A few of them came of age at a time when unions were considered heroic, and they can’t shake that narrative, so Lancellotta falls immediately into the character of suspicious troublemaker. The younger journalists have recently emerged from a K-BA system that is more about indoctrination than education. Others are fully onboard with the progressive movement of which government unions are a driving organizational force. Some are probably (consciously or otherwise) wary of landing on the disfavored list of the most powerful people in the Ocean State.

As a purely economic decision, remaining in a teacher union makes no sense for any individual teacher, yet it’s extremely rare for teachers not to opt in. This results from a multilayered campaign to prop up union membership. The broadest layer is of inculcated ignorance, whereby teachers simply don’t know their rights. Colleges of education certainly won’t explain their options to students, and journalists help to keep teachers from having reason to investigate for themselves.

As the layers become more focused, they involve deception about what being in or out of the union entails. Another layer lays deliberate obstacles to being non-union (e.g., the district office simply begins deducting dues, and the superintendent tells the teacher she has to discuss the matter with the district’s union leader, who imposes improper obstacles). The most pointed layer includes experiences such as Lancellotta’s, which send warning messages to any teachers who still come to the conclusion that avoiding the union is the right decision for them.

Whatever individuals’ conclusions might be, a fully informed citizenry would be familiar with this reality and understand its connection to school failure in Providence and elsewhere. Unfortunately, as Carlson explains, a well funded and influential industry is dedicated to ensuring that the public is not familiar with any reality but the one ideologues want to be true.

Featured image by Kristina Flour on Unsplash.

[Open full post]Clearing out some old links reminded me that Rhode Island’s “pay equity” statute goes into effect this year, as Jack Kelly wrote in Forbes in late 2021. While generally supportive of the legislation, Kelly did acknowledge the potential for “unintended consequences”:

According to Joshua Nadreau, a partner in the Boston office of the labor and employment law firm Fisher Phillips, Rhode Island’s statute is “one of the few pay equity laws that targets protected classifications other than sex or gender.”

Nadreau posits, “This may add considerable burdens to employers who may not have historically tracked this demographic information. How many employers track the religion or sexual orientation of their employees? One of the questions I have is whether an employer will be held legally responsible for a pay disparity between various protected classes if it doesn’t even possess the information to make that determination in the first place.”

More insidiously, “merit” is a tricky thing. It’s not always easy to articulate why an employee is a “rock star,” and managers can easily disagree. A key component of judgment for a manager is whether an employee is a personality match for that manager, and such subjective factors will now leave employers vulnerable to lawsuits. Stack these requirements onto the side of the scale in favor of employers’ not expanding or staying in Rhode Island. This sort of legislation makes employees more costly while doing nothing to make them more valuable.

Dragging down the economy isn’t the only reason to be wary of policies that seek to “correct” social outcomes. I recently had cause to run a pay-related regression analysis that had sex as one of the variables. The analysis did find that women make less when starting a new job, all else equal, although the “all else” was missing some very important variables (like industry). However, that’s the subject of a continual back-and-forth. The overlooked consideration that piqued my interest was that the gap is much less significant for younger women than for older ones.

Add in the fact that younger women are more likely still to be pursuing education while their male peers are more likely to start working full time sooner (often in jobs with lower ceilings), and it’s entirely possible that young women actually have an edge. In 20-40 years, we could see a complete reversal and worsening of the pay gap.

I’d need to do more research before insisting that’s the case, but the point is that it’s not even a matter of discussion. The unintended consequences, in other words, could be massive, devastating, and long-standing when a moral panic produces reckless social experimentation by a cultural elite with little ability or appetite to think a contentious topic through completely.

Featured image by Lucas Sankey on Unsplash.

[Open full post]On WNRI 1380 AM/95.1 FM, John DePetro and Justin Katz discuss:

- Duplicate votes: rare and easily caught or the tip of the iceberg?

- McKee extends the “emergency.”

- Why doesn’t anybody qualified want to run for Congress?

- Ray McKay’s entry for Senate.

- Bud Light steps into the quiet rage.

- McKee’s binding to Biden.

On WNRI 1380 AM/95.1 FM, John DePetro and Justin Katz discuss:

- The high price of detecting voter fraud.

- Neronha and McKee’s strong relationship of occasional “hellos.”

- AG’s Twitter serving as his platform for backlash.

- Cranston St. Armory’s plan to evacuate warming shelter and relocate families.

- Raimondo and government inevitably sneaky industrial policies.

Featured image from Shutterstock.

Guests: Dora Vasquez Hellner, Army veteran

Alyson Matera, Rhode Island National Guard

Host: Darlene D’Arezzo

Description: Our guests represent a broad range of years of service and experience. Dora Vasquez Hellner is retired with 23 years of military experience. Alyson Matera is active and has 8 years of service to her credit. They share common experiences as well as distinct and different service. A brief history of women in the military is not only interesting but also remarkable. They also comment on the challenges women have faced over time and the alarming experience of sexual trauma some women have experienced in military serviced.

Artsy people’s complaining about gauche wealth-culture is nothing new, but something about this complaint by progressive podcaster and musician Bill Bartholomew struck me as oblivious of the obvious:

Working late on Friday to frame out a roof on Ocean Drive 15 years ago, while watching BMWs roll by, I had similar thoughts. But I also appreciated the consistent and interesting work available to me as a carpenter, as well as the beauty of location and architecture around me. The same qualities attract many tourists each year.

Note, however, Bartholomew’s snobbish juxtaposition of “hooting and hollering” from people he looks down on and the “vibrant” lives of people he prefers. His artist’s view might move toward my artisan’s perspective if the funding structure of the arts hadn’t shifted so dramatically from the patronage of the wealthy to the dole of the government.

Progressives and socialists (if there’s a difference, at this point) fall into the trap of thinking that government control will change the aspects of society they want changed while preserving those they value. They can be surprisingly reactionary about the latter, tightly gripping the false beliefs that (1) their views will guide government (which they won’t, even if politicians’ ape their slogans) and (2) that government is capable of nuanced and fine-tuned control of progress. It isn’t. Government is a blunt tool.

The trends in Newport and across the state are the consequence of the choices Rhode Islanders have made through their government, but the ability to imagine an outcome does not mean it’s really available. You cannot have the past back. You cannot freeze the present. The city is going to change one way or another. If government seeks to preserve its architectural character, then the prices will go up. If activists demand housing prices freeze or go down, the city must change.

I’ve said this before, but it bears repeating: A crucial element of Rhode Island’s charm is its diversity of neighborhoods — the unique character of small areas. That doesn’t happen with planning; it happens with freedom, and freedom brings change, leaving us only the choice to adapt.

Maybe the entirety of Newport will become AirBnBtown, but then workers will be able to demand a premium for their travel there. (More economic liberty might produce innovative ways to get them to work and reduce the traffic.) Or maybe the economics of property value will make lower-cost housing profitable for developers in ways that will make the trust funders complain.

My prediction is that if we stop trying to control everything and let niches develop, taking enjoyment from the excitement of watching the future unfold, our attitude will change as a community. Sure, everybody gripes a bit as things change, but if they can carve out a place, even the things they gripe about gather a familiar warmth around them. And if the change is fundamentally incompatible with any given person’s preferences, maybe Newport isn’t the place for him or her. Why should we entertain such people’s demand that everybody else accommodate their tastes?

Featured image from Shutterstock.

[Open full post]As an undergrad, back when the Internet was still brand new, I decompressed by reading through Stephen King books borrowed from the Carnegie Mellon library and noticed something. One of his recurring techniques was to imagine the familiar as the monster. Cujo was a dog. Christine was a cool car. Firestarter was a little girl. The title character in Cycle of the Werewolf, which became the movie, Silver Bullet, was the local priest.

As a non-King movie, Child’s Play, showed, the idea caught on, and naturally, artists’ explored the opposite: heroes whose appearances or identities are typically associated with villains.

One of the defining peculiarities of the present day is that this species of literary device has become written into our society and is affecting our ability to assess reality. Consider this headline: “‘Drag Mom’ Who Mentored 11-Year-Old At Satan-Themed Pub Sentenced For 11 Child Sex Felonies.”

At this point, we’re being encouraged to actively suspend our common sense and long social experience to avoid harm before it’s done. What do we think is going to happen?

[Open full post]Jeann Lugo was acquitted in November of simple assault against Jennifer Rourke at the State House melee last June. The other criminal charge against Lugo, disorderly conduct, had been dismissed in August.

Now a three member panel of police officers, in a process arising out of LEOBOR, has unanimously voted to set aside the firing of Officer Lugo ordered by then-Providence Police Chief Hugh Clements. Current Providence Police Chief Colonel Oscar Perez has indicated he will abide by the panel’s decision.

Heartfelt thanks to both Judge Joseph Terence Houlihan (especially Judge Houlihan) and to the three members of the panel for wisely looking at all of the evidence and delivering justice to a falsely accused man.

Two matters stand out for me.

> Now that Jeann Lugo has been held to account, Jennifer Rourke needs to be held to account for her actions of both that night and the aftermath. She is clearly seen (major credit to WPRO’s Tom Quinlan for posting this full video) assaulting both Lugo and another man by violently shoving him. And she lied under oath twice about her actions to investigators.

> Jean Lugo should unquestionably sue Bill Bartholomew for defamation including maximum damages. None of this – a mob ginned up against Lugo leading to his being criminally charged; former Police Chief Hugh Clements rushing to order the termination of Lugo; the criminal trial of Lugo; the baseless damage to his reputation – would have happened had Bartholomew not created and released a very short video of the incident that was so extremely edited that it was a palpable lie.

A video that deliberately cut out what preceded Lugo’s actions in using an open-handed defensive technique against Rourke.

A video that cut out Rourke repeatedly laying hands on Lugo and physically restrained him from trying to defend Josh Mello, who had just been sucker-punched.

A video that conveyed the completely false story that a man had struck a woman; a white cop had struck a black person; a male candidate for public office struck his female opponent – out of the blue, for no reason.

I contend, in fact, that Lugo actually has an obligation to file a defamation suit against Bartholomew because such litigation is a righteous and powerful way of discouraging the future creation of similarly false, harmful videos by people hungry for clicks and attention and, specifically in this case, by someone who has reached for stepped up credibility by conferring on himself the title of “Journalist” – something that, remarkably, Bill Bartholomew has done.

[Featured Image Credit: screenshot from Tom Quinlan’s video of the melee.]

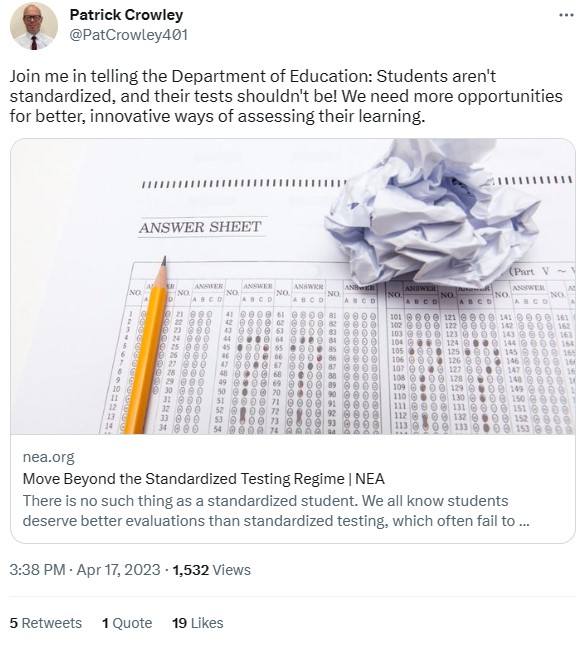

[Open full post]Sometimes the cognitive dissonance from special-interest ideologues’ commentary is so strong it’s difficult to know whether they’re brainwashing, trolling, or both. Consider this tweet from Rhode Island labor union executive and progressive activist Patrick Crowley:

Before Crowley moved up the union-organizer ranks and was still specifically with the National Education Association of Rhode Island, I had occasion to argue policy with him from time to time, and he was not shy about deploying the standard talking points. Ask a professional union advocate why super-effective teachers shouldn’t be paid more than mediocre or marginal ones, and they’ll give you some variation of: “We advocate for an excellent teacher in every classroom.”

In short, they respond with a dream in which all professionals in an occupation can be standardized at the very highest level, evading the fact that a standardized, one-size-fits-all contract will be more attractive to those who are below the average than above it.

Interesting arguments can be had about this topic, but notice the contrast with Crowley’s tweet. Why couldn’t supporters of standardized testing just say: “We advocate for excellent results for all students.” They do say such things, and the NEA’s response isn’t about the complexities of testing, evaluation, and accountability, but is a propagandistic appeal to emotion: “there is no such thing as a standardized student.”

I’m no fan of a system that relies on standardized tests as more than one of many datapoints, but the way the public school system is structured at the moment, such tests are the only option for accountability. Naturally, the teacher unions oppose any measure that might begin to expose (1) the ineffectiveness of the system that treats them so well and (2) either the differential effectiveness of teachers or the irrelevance of teacher effectiveness.

A better approach would be to move away from standardization altogether — including standardization of teacher compensation as well as standardization of enrollment, by which I mean assigning children to schools based on where they live.

Schools that operate according to standardized contracts and enrollment will find it easy to come up with non-standardized reasons that every child is benefiting from their services, but the parents and the public can have no trust in their proclamations. The alternative is to allow schools to manage their teachers according to the non-standardized measures of effectiveness that any organization can develop and then allow families to assess and choose schools according to their own non-standardized priorities.

Featured image by Niamat Ullah on Unsplash.

[Open full post]