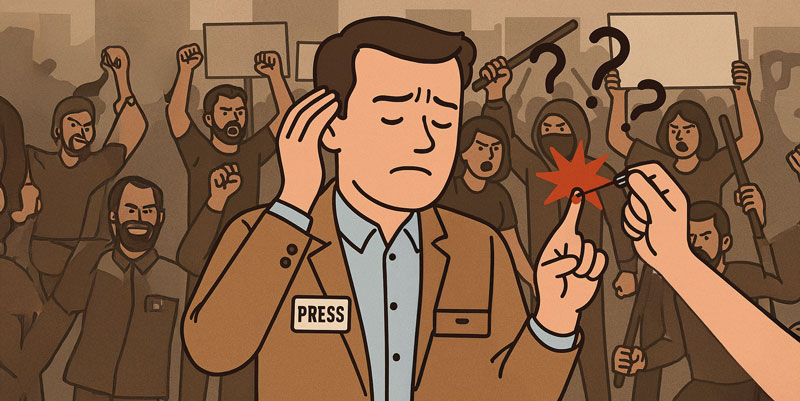

Politics This Week: Messaging in a Trustless World

John DePetro and Justin Katz review the latest in Rhode Island politics.

Politics This Week: What They Find Interesting (And Not)

John DePetro and Justin Katz discuss the stories we don’t hear and should.

Politics This Week: The Wall of Insider Silence

John DePetro and Justin Katz highlight topics RI’s insiders try to keep behind the scenes.

Politics This Week: The Madness We’re Not Allowed to Handle

John DePetro and Justin Katz discuss the many charades insiders want RI to perpetuate

Politics This Week: What They Find Interesting (And Not)

John DePetro and Justin Katz discuss the stories we don’t hear and should.

Politics This Week: The Wall of Insider Silence

John DePetro and Justin Katz highlight topics RI’s insiders try to keep behind the scenes.

Politics This Week: The Madness We’re Not Allowed to Handle

John DePetro and Justin Katz discuss the many charades insiders want RI to perpetuate

Politics This Week: The Business of Corruption

John DePetro and Justin Katz trace the evidence that corruption has become the business of government.

Politics This Week: The Bitter and the Comfortable

John DePetro and Justin Katz review the latest political news in RI.

One could pick apart on its own terms Nicholas Ferroni’s commentary suggesting that most states can’t be trusted to run their own education systems and “education is not an expense; it’s an investment”:

For context, Ferroni is a teacher in New Jersey who calls himself an “activist” (apparently for left-wing social causes) and moonlights as a paid speaker. He takes it as written that the federal government is a net positive to education, which many of us would dispute. Indeed, his case that there is already a wide gulf in the success of schools from state to state brings his assumption into question. His faith in the value of teachers unions amplifies the need to question his assumptions. In Massachusetts, which he calls out as an exception where the state government can be trusted with education, the success is directly attributable to reforms decades ago that reduced the unions’ power (which have been softened with predictable results).

The problem with insisting that “education is an investment” is that many institutionalized and powerful people believe it should be a unique form of investment whereby the simple fact of adding money increases profit, and wherein demanding accountability from the people who take that funding on the promise of making the investment bear fruit is an affront.

Education needs more accountability and less meddling from activists inside and outside of government.

The great DOGE Authority Panic of 2025 appears to have passed, but in case you’re still interested (and to have it searchable on this site for future reference), lawyer Tom Renz’s review of the legal basis for the Department of Government Efficiency is worth a read.

Here’s the Providence Journal headline: “Numbers show RI undocumented immigrants a small slice of those getting benefits. What we know.”

Here’s one of the shocking facts that journalist Katherine Gregg did the work to uncover:

Medicaid payments on behalf of those without Social Security numbers totaled $55.4 million last year, including the $16,106,050 paid for those officially determined to be undocumented immigrants.

The article proceeds to dismiss entirely all but the $16 million and then to contextualize that number as a drop in the state’s Medicaid budget.

Now add to the total another $12 million for various welfare benefits from the state, and we get up to $28–67 million total. In what other type of story would the reporter treat that amount of money as insignificant and the newspaper pass on an eye-catching headline… in an era when it needs all the attention for its work that it can get??

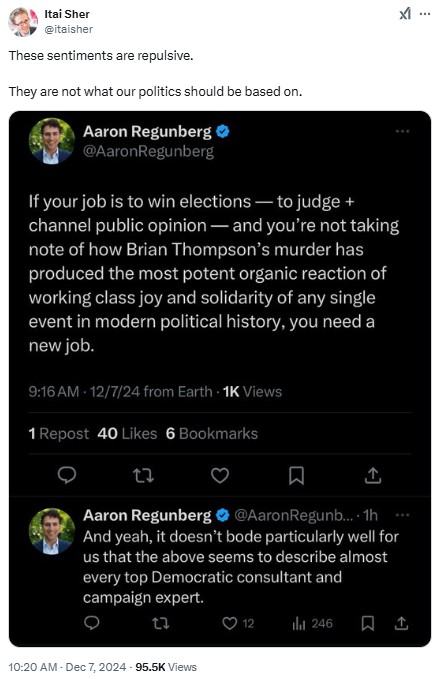

The fabricated nature of this tweet’s content is just one example:

To be sure, that isn’t the most egregious example I’ve come across, but I particularly wanted to capture a statement relegated to the very end of the article, coming from one of only two local sources cited for the article, William Worthy, of Big Bear Hunting & Fishing in Glocester:

“Maybe [Trump’s tariff policy] opens the door for some local people to have local-made bait instead of bait coming from other countries,” Worthy told 12 News. “I’d rather push the locally made stuff if I can’t buy the stuff from China anymore. I think it will create other opportunities.”

At the risk of arriving late to the news cycle of a couple weeks ago on the hierarchies of love, I wanted to offer an adjustment to Matt Walsh’s perspective, with which I mostly agree:

The point is well taken that it’s easier to love “people” in the abstract than to love particular people (particularly when doing so leads one to advocate for things that one wants anyway). Nonetheless, if the term, “love,” means willing the good of the other, it is certainly available to both distant and aggregated people — the broader humanity. However, the closer a person is to environments that we can actually influence, this willing the good increasingly requires action.

Progressive policy is characterized by three qualities that bring the reality of their “love” into question:

- It is only marginally more specific (if at all) than the love that most well-meaning people will have for people they don’t know.

- It tends to impose obligations on people other than the progressives who claim to care so much.

- It implicitly imposes progressives’ beliefs about what is “good” on everybody else, including the constituencies they patronize.

Of course, for many progressives, we could add in the fourth characterization that the policies conspicuously benefit them in some way.

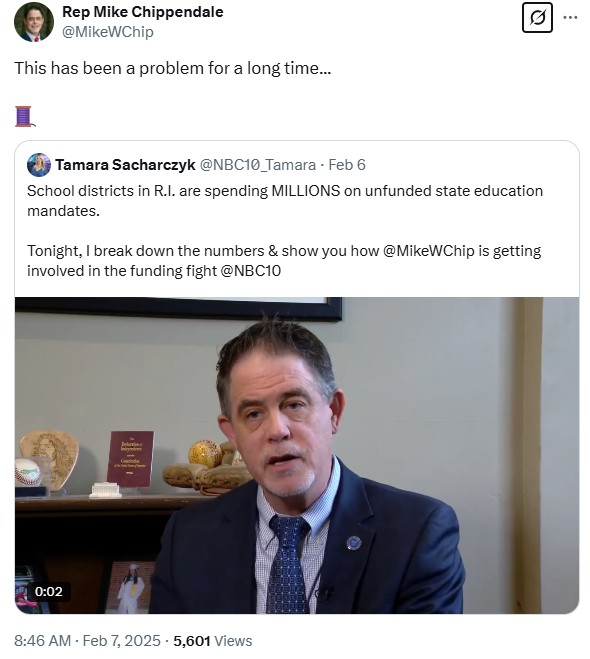

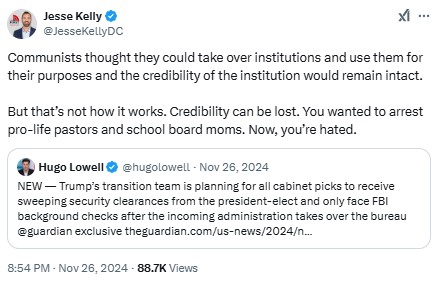

This…

This…